Metamorphosis: The Contours of Your Embedding

Rip yourself out from one layer of the world, dig into another

Their is a fatal flaw in all the cybernetics-flavoured developmental psychology I’ve been reading. And once you see it, I hope that you can’t unsee it.

I Wish We Had a Shorter Word for “Cybernetic Organisms”

The very heart of personal development lays in an individual’s alternating phases—systole and diastole—of differentiation and integration with the environment, developing in complexity.

You get into something and become it. Then you get some distance from it and, often painfully, get self awareness of having been it. It goes from being you to something you have. It’s a part of you, but you are now more than it. You grow more complex. The old you and the new you are more tightly integrated as a result. And then what doesn’t work is differentiated again. And then an even newer you runs circles, like a rings of a tree trunk, around the old you.

Rip and heal. Breakdown and Breakthough. That’s growth.

You were your emotions when you were a kid. Now that you understand them and often control them, you merely have them. Same with habits. Then you were your wants and needs and interests when you were wasting money to buy shit—clothes and music and fan merch and flags—to make an identity for yourself. Now you merely have interests, but you are more. You were your job when it was your life—now you have a job and a life. You were an activist when you only socialized with “your people,” and fought with them as one of them. Now you have interests and affiliations, but can think and work and live across them. You were half a dialectic, now you internalize the dialectic.

Another way of saying that you were being a thing in the past is to say that rather than having those things, they had you. Before you developed control and agency over them—which is to say before you gained self-control— your emotions had you, your habits had you, your fandom had you, activism had you, your job had you.

This is cycle of differentiation and integration is cybernetics. It is the relation of some part of the system to a whole system, systems thinking. Cybernetics underwent its own development since the 1940s which you can read all about it in N. Katherine Hayles’ How We Became Posthuman (1999), a book which is still central in the critical humanities today. Critical theory is built on cybernetics—the science of control.

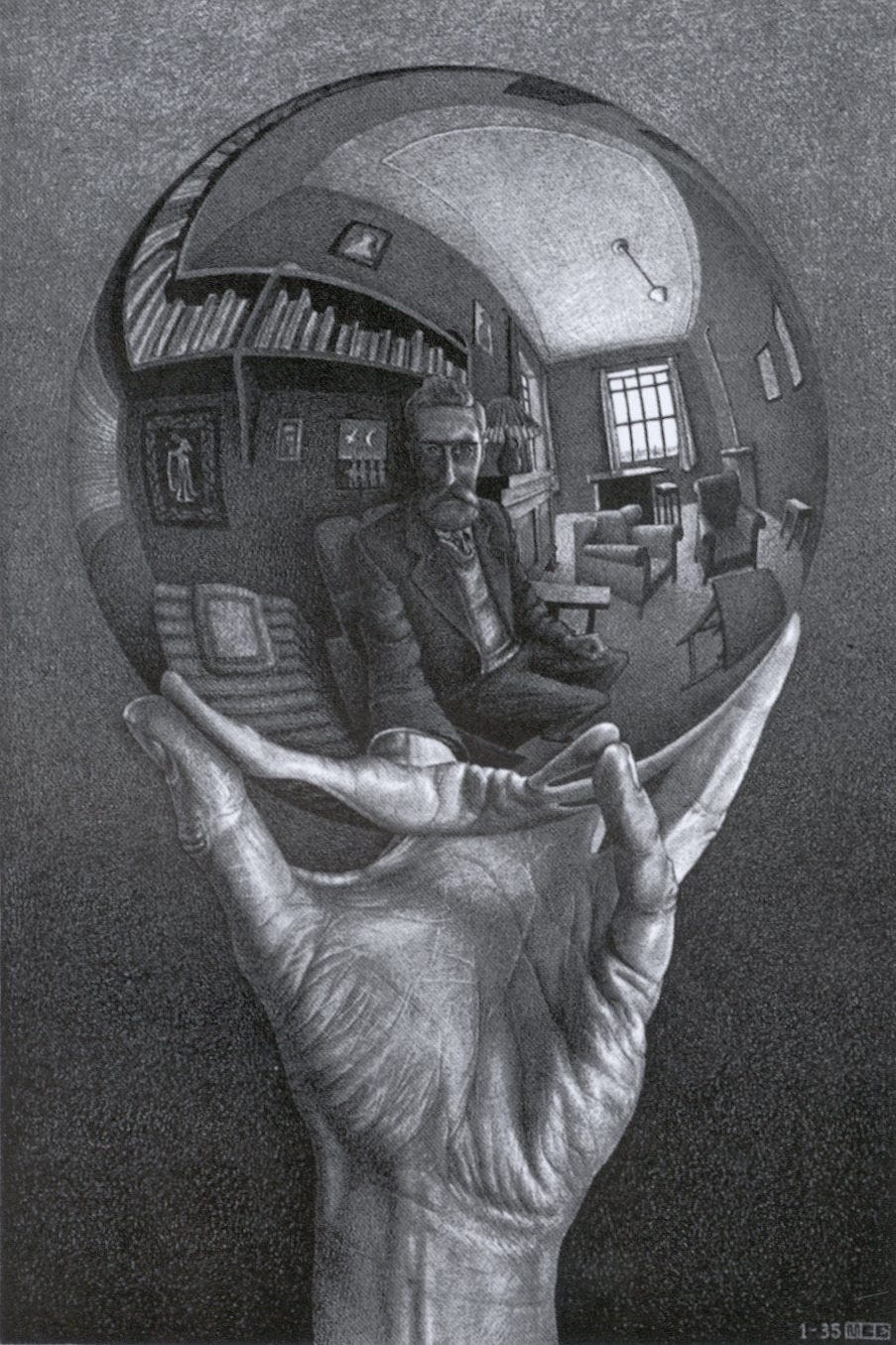

Read Hayles. When you do, you’ll see how when cybernetic theory shifted from governing systems from the outside, toward governing a system which includes itself as part of the system, things got weird. Recursion does that.

Science couldn’t go on forever pretending it spoke some from neutral place outside of the world—but including yourself in the world you study is the million dollar problem.

Autopoesis, or self-creating systems, is the term for the solution still central to cognitive science today. It is well explained, albeit very abstractly, in John Vervaeke’s 50-episode lecture series on The Meaning Crisis. Complex systems create themselves through being “embedded” or seeking “fittedness in the environment,” in an evolutionary sense. They grow, in other words, as agents within an arena, devloping as I said developmental psychology says that you do.

That term Meaning Crisis, popularized as the title of Vervaeke’s series only a few years ago, has launched a million ships of online intellectuals, all alienated from society-proper in some way, and all drawing on myriad foundations.

Leaders and Teachers

The internet today is flooded with individuals who have differentiated from mainstream institutional thinking or political identities who are in various states of organization, personal development, social acceptability and, frankly, sanity. They’re all addressing the crisis in some fashion, whether they are aware of it or not. Most of them seem to have taken up the hero’s journey—sometimes in all its deluded, grandiose forms. A very scant few who have gone this route, as we’ll see that my friend Bob has done, have had this work in their favour.

In the main, let’s differentiate between two paths, leaders and teachers.

Some such heroes position themselves actively as culture-warriors whose degree of development is to be witnessed, learned from, and copied. The active warriors are busy doing things publicly, and hope people copy them. Primarily they just amass spectators, cheerleaders, and parasitic analysts. They teach primarily through mimesis: monkey see, monkey do. Their attitude rubs-off on people. Those who are inspired to copy them learn from doing for themselves.

You already know who these people are, because they make the news—or at least trend highly on social media.

Many, many more passively—and impotently—try to inhabit a role as a guru or shaman. In their writing, they position themselves over multitudes of lost and disaffected eSouls, seeking to teach them directly, by personal address. These self-styled teachers rely on students studying and learning conceptual frameworks and history—one on one coaching or long discussions or reading many books is part of this tradition.

In course terms, the leaders have something, or are had by something. Either way, their is a stability to them. The teachers are projecting their in-betweenness, their transition, and aiding to help others transition between equilibria, to grow.

This of course suggests that one person can take both roles at different times or in different contexts—but compared to all the advice out there about how to be a leader, popular wisdom on taking on teacher role is much harder to come by. “Why does nobody read my stuff? I’ve given you all the answers!” aspiring midwives-to-being might lament, to nobody listening.

One problem may be that these new shamans are very, very late to the game. Consciousness raising cults, like those coming out of The Esalan Institute in the ‘70s (where OG cyberneticist Gregory Bateson found a home for his ideas) have been doing this for nearly as long as cybernetics has been around. And, of course, “schools” masquerading as occult or ancient traditions like Kundalini which have been around far longer can integrate new ideas easily, their cult recruitment aided by the romantic appeal of mysterious “tradition.”

Another problem is the loathing of selling out—commoditizing one’s self. The more benign, culturally acceptable dressing for the shamanistic role is something like personal coaching, or motivational speaker, or self-help author.

I’m grappling with this myself, having gotten rather pissed off two weeks ago reading a recent airport book for business managers by a developmental psychologist whose early work I had just admired.

(Of course, after a few days of examining my rage I realized that McLuhan had sold out too. He even wrote an extremely good business-management book called Take Today: The Executive as Dropout—which is nigh unreadable to anyone with a business degree who wasn’t also an English Literature post-grad. I guess the highly addictive, epidemic ‘self-adulating testimonials ⇨ case-studies ⇨ try-it-yourself!’ formula hadn’t been cooked up in the book publishers’ laboratories yet.)

Formulas for Change—Without Ground

Both active exemplary leaders and passive, pedagogical teachers are essential to growth. The former show you what you aren’t yet, but what you could be. The latter, in the ideal case where they aren’t some variant of cult leader, help you in the transition with direct, personal help. Most of us get both of these sorts of social support merely from our daily life and friends and family. Just exposing one’s self directly to more experienced people will provides all kinds of support when you’re ready to receive it.

But one thing is clear. In every formula for personal growth, maturation, development, consciousness raising, etc. which is at least half-baked, you can perceive the basic premises of cybernetics—implicitly or explicitly, correctly or incorrectly.

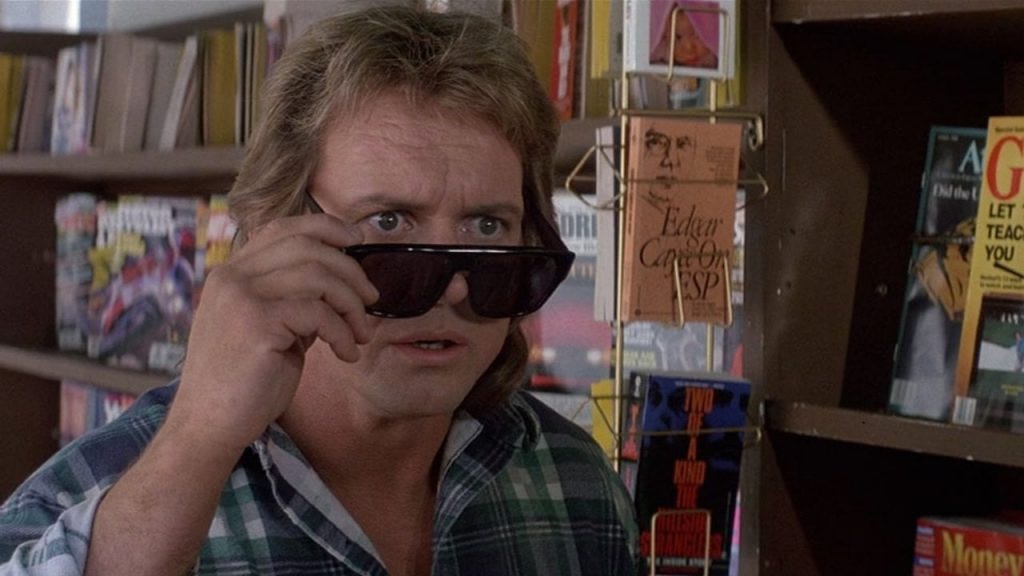

As I explained in my first large writing on developmental psychology and cyberspace, Cheating at Peekaboo Against a Bad Faith Adversary, academic video game criticism uses cybernetics extensively in its understanding of players merging with game-worlds.

The hubris of these activist academics and their acolytes in journalism who propounded this exact theory drove much of the under-analysed outrage behind GamerGate in 2014, as I told readers of Default Wisdom. The insinuation games journalists kept making was that trying to master or win at videogames—differentiation—is male-coded and morally bad, and that empathetic merging and co-becoming with video games—integration—is feminine-coded and good. The authority I cite in Peekaboo called it the dichotomy of male hackers vs. female cyborgs.

It seems the intention in video game criticism is to build an intellectual edifice to better socialize students in schools through lucrative, tax-payer funded educational software purchases which would lead to funding for the scholars versed in their critical methods. Unfortunately, the familiar cultural figure of video gamers as competitive men made investors and institutions skeptical about games in classrooms. Games had to become arenas for personal psychological development and emotional learning, not challenges to surmount. Children, then, should be cyborgs, not hackers.

But for our purposes here, the academic theory GamerGate reacted to was just another example of applied cybernetics—merger and separation, integration and differentiation. But it’s a contemporary case, and a real one. It underlies lots of the fights between parents and schoolboards regarding curricular content, and lots of the reaction to applied social constructivism. And that’s the weak spot.

In Psychotherapy as a Developmental Process (2009), Basseches and Mascolo provide a contemporary view of where developmental psychology has gone since Piaget. It’s all very good, dealing with the dialectical processes between self and environment which drive the alternations of differentiation and integration toward complexity. In the third chapter, however, where they lay out their unified “coactive systems model of psychotherepy and development,” they reveal the ingredient which fatally flaws the science.

The coactive systems approach builds upon three main traditions. These include Piagetian and neo-Piagetian constructivism (Basseches, 1984, 1997a; Fischer & Bidell, 2004; Mascolo & Fischer, 2006; Piaget, 1970a, 1970b, 1985), sociocultural and social-constructionist theory (Cole, 1996; Gergen, 2006; Rogoff, 1990; Shotter, 1997; Valsiner, 1998; Vygotsky, 1978; Wertsch, 1998), as well as contemporary systems theory that incorporates embodied conceptions of development (Bråten, 2007; Gottlieb et al., 2006; Lewis & Granic, 2000; Thompson, 2007).

As I’ve tried to express over and over again, we are embodied creatures. The titles cited in the third “embodied” tradition quoted above seem to discuss mirror neurons, biology, emotions, and otherwise the “hard problem” of mind’s relation to our bodies as physical objects. This is the complete opposite of what I refer to by embodiment—it is embodiment in a vacuum. In a null space. It is, as McLuhan said over and over, figure without ground. It is disembodiment, or the discarnate state—something I am very familiar with.

John Vervaeke pushes the conversation far ahead of this situation with his focus on the “agent-arena” relation. Implicitly, the arena we live and play in matter just as much as our own bodies do when it comes to how we develop—I’d argue it matters more, since it’s all the more varied. Of course, we’ve all heard about “environmental” factors in development, especially in nature nurture, but that brings us to the other problematic “tradition” in Basseches and Mascolo’s coactive system.

To use the phrase “embodiment” to discuss the body itself is absolute navel-gazing. Can we please just stop trying to fight the mind-body split, the Cartesian subject, by insisting upon biology already? Please? Propositional arguments will not fix the fucking homoncular fallacy. You can not logic someone out of the innate feeling of their sensation of being divorced from their body. “Look! Brain science says that they sensation you feel isn’t true!” has never, ever worked. Because, as McLuhan correctly diagnosed, the mind-body split is caused by our embodied relation to the rest of the fucking world, the total environment itself. The etiology of the mind-body split lies in the arena, not the agent.

(uh oh, I’m getting worked up again…)

The agent—your personally agency, you’re ability to act—is co-constituted by, dictated by, your merger with or mastery over your environment, which today means, more and more, your computer. As I discussed with the Free Software Foundation last year.

Mirrors reflecting mirrors reflecting mirrors…

Did you notice Kenneth Gergen, social constructivist/scholar of the media “saturated” post-modern subject, listed in the citations for the second “social-constructionist” tradition?

(There are a lot of conflicting style-guide advice about “constructivism” vs. “constructionism.” But I personally use -ivism for post-modern conceptions like those of Gergen’s. I use -ionism to refer to Seymour Papert’s applied Piagetian pedagogy, seeing as he opposed his classroom constructionism to traditional “instructionism” by rote memorization, drills, and the like.)

The social environment has become, for better or worse, the virtual entirety of the environment for analysis in every field drawing on developmental psychology. This is what social constructivism is. It’s a world where everything around you is understood via by who you talk to about it, who makes it for you or sells it to you, and who you pay to fix it for you.

You ask Google a question about the purple splotch growing on your thigh? That splotch is now “socially constructed.” A restaurant does A/B testing on ingredients to make the perfect salad, drawing on sales data and questionnaires? That salad is now “socially constructed.”

When you buy an ointment to treat that splotch, or when you rub an organic garlic clove on it, you’re doing so because of what someone else told you. When you eat that salad, you’re eating something from the synthesized mind of all those test subjects.

I’ve often detailed my approach of going down the stack, back to materiality, using computers, but let’s stick with salads. Let’s say you don’t buy a salad, you make one yourself. Okay, but your decision about where to get your ingredients, who to pay for them, is socially constructed. So then you go further down, you grow them yourself! But now where are you getting your soil? Your seeds? The land for your garden? The means of keeping squirrels out of it? Who do you trust?

Obviously we are all interconnected—I’m not trying to say that we aren’t. The difference between a salad and a computer is that we make our bodies out of what we eat—we measure and shape our relation to our bodies, our family, our jobs, institutions at large, and the whole world through our computers.

I often see young people sitting on the public bus staring at a live GPS map the entire time, waiting for their stop, terrified to go off route and find themselves embodied in a city somewhere. They exist on the screen first. Their embodiment is the little GPS arrow-sprite on the center of the screen. That is them. They are related to the bus, the roads, the street names, the architecture, the people on the street only secondarily, or vicariously, through that map. If they pass a restaurant, the screen tells them about it. Of course, passing through the world this way, they’re never without headphones. I used to be the same way.

That’s what social constructionism is. It’s being where your embodiment and what you do is mediated through society. And society is your proprietary, commercial, surveillance capitalism Macintosh/Google/Facebook tracking device. There’s a damn good reason I put an effort into making it to Boston to present at the Free Software Foundation’s convention last year: personal development itself is being oriented into deeper and deeper cybernetic splicing into cyberspace.

The contours of the embedding of your body and mind—your being—into the material world is being re-routed into the content of the computer. This is why I see the banning of smartphones in classrooms, as proposed by Jonathan Haidt, as exceedingly important. His explanations why are nearly useless as explanations, but excellent as the sort of rhetoric which may actually lead to policies being enacted. Nobody in power would listen to my arguments because they come from completely out of the blue.

I am not embedded institutionally at nearly any level. That’s kind of the point. I work a part-time job from which I am near-completely uncancellable. People living within institutions—corporations, governments, schools, entertainers, journalists; more or less all of “society” proper—are unable to differentiate from the social constructions which bind them. Their bureaucracy, their networks, their pocket books. When they try, they become a threat to the greater-whole to which they are a part.

In their world, they are mirrors reflecting mirrors reflecting mirrors. There is no original—this is what Baudrillard taught us. Their environment is each other, where each other is barely face to face. It’s mostly mediated through communications media like emails, memos, videos, posters, influencers, etc. and more abstract, and indirect forms. All the tools of “metrics” I discussed in my FSF talk comprise the arena for agency today. Not the real world of physical objects, and face-to-face people. Personal property isn’t really own3d when it can only be reliably used or fixed via a credit card. Such commodities don’t, then exist directly as physical objects, but objects whose permanence is mediated by someone else. And I’m not merely stating a logical proposition—your body feels that. Your senses feel that. The fragility, the unreliability of things you don’t actually control inheres directly in your phenomenological sense of the thing itself.

Is there anything you own, that you don’t quite feel like you own, as much as your computer? Is there anything else you need to get more under your own control? Do you now understand McLuhan’s maxim “The user is the content?”

Long-time radio personality Bob Dobbs—with whom I myself have been a long-time cohost—has developed a great way of talking about embodiment this with far more nuance than the social-absolutism of contemporary, “respectable” fields who draw on social constructivism, semoitics, information theory, and the like. Of course, Bob stays safely on the outside by saying making many more ludicrous, disrespectable observations and claims—but that’s the fun of the trickster archetype.

It should be easy, at this point, to tie together what I’ve been saying above with his five-bodied model, as so:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Less Mad to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.