If you were online around the same time I was growing up, you knew all about Dr. Gene Ray’s Simultaneous 4-Day Time Cube. Maybe you saw him on TechTV in 2007, where he justified his righteous mission to a belittling host.

Beyond all doubt, Dr. Gene Ray is the internet’s archetypal schizoposter, asFred Knudson ’s fine documentary reveals. From an archive of the original timecube.com, fresh as the day I first read it twenty years ago:

God guise for Unicorn

scam, enslaves 4 Day

cube brain as ONEist.

Vilify teachers - for

Unicorns swindle Tithe

from 1 Day Retireed

***********************************************************************

Till You KNOW 4 Simultaneous Days

Rotate In Same 24 Hours Of Earth

You Don't Deserve To Live On Earth

Americans are actually RETIREED from

Religious Academia taught ONEism -upon

an Earth of opposite poles, covered by Mama

Hole and Papa Pole pulsating opposite burritoes.

The ONEist educated with their flawed 1 eye

perspective (opposite eyes overlay) Cyclops

mentality, inflicts static non pulsating logos

as a fictitious unicorn same burrito transformation.

Let’s not examine this too closely—except to note that the spelling of “burritoes” arouses more than just hunger. In fact, it also suggests a different, more celebrated text upon which we might consult an interpretation.

“Willed without witting, whorled without aimed.”

Nearly a century prior to Gene’s internet fame, the English Modernist movement began with the publication of T.S. Eliot’s poem The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock in 1914. Soon after the book form itself was innovated, toward simultaneously all-comprehensive and nearly-incomprehensible ends, by the most encyclopedic and poetic writer the English language has ever known.

Just gaze upon this single representative sentence from page 230 of Irish Modernist James Joyce’s circular, 628-page capstone novel Finnegans Wake—actually, don’t just gaze at it, read it out loud as Joyce intended:

He would si through severalls of sanctuaries maywhatmay mightwhomight so as to meet somewhere, if produced, on a demi panssion for his whole lofetime, payment in goo to slee music and poisonal comfany, following which, like Ipsey Secumbe, when he fingon to foil the fluter, she could have all the g. s. M. she moohooed after fore and rickwards to herslF, including science of sonorous silence, while he, being brung up on soul butter, have recourse of course to poetry. With tears for his coronaichon, such as engines weep. Was liffe worth leaving? Nej!

In consulting Roland McHugh’s Annotations to Finnegans Wake, we can pull on the better-part of a century’s work of Joyce scholarship interpreting this passage.

We see, for instance, that several lines by Joyce are adaptations of lines from a book titled Woman: The Inspirer by Edourd Schuré. Joyce turns “the sublime art of sonorous silence” into “science of sonorous silence.” Schuré also apparently quotes his friend, the German composer Richard Wagner. When Wagner’s phrase “recourse to poetry” becomes “have recourse of course to poetry,” there is (of course) a recourse of the word “recourse.”

McHugh here also reminds us of the importance of ricorso to Gimabattista Vico, who resonates throughout the Wake (and McLuhan’s work with his son Eric, Laws of Media.)

The Irish folk song Phil the Fluter’s Ball resonates in “to foil the flutter,” and the phrases “being brung up” and “soul-butter” are taken from Huckleberry Finn, chapters 28 and 25 respectively.

Milton’s “Tears such as angels weep burst forth” becomes “With tears for his coronaichon, such as engines weep.” McHugh tells us that corónach is Italian for funeral dirge. However, to me, Joyce’s word “coronaichon” immediately suggested the French cornichon, which means pickle!

Salty, pickling tears fits the passage much better I think—which is not to say a funeral dirge wouldn’t bring them out!

And again, I am left hungry.

Would you give me a reference?

Dr. Iain McGlichrist has spent years amassing scientific and medical evidence to demonstrate the coherency of conceptualizing the brain in terms of hemispheric specialization. At a time when many cognitive scientists claim that “left brain, right brain” discourse is oversimplified, McGilchrist hits back hard. His books, the 2009 The Master and His Emissary and the 2021 The Matter With Things are replete with case-studies and citations from medicine, psychology, and cognitive science.

If it is true that most talk today of brain hemisphere lateralization today comes laden by business-consulting grifts or new-age nonsense, then it is all the more important that a careful expert like McGilchrist purify the language and clear out the errors.

Here is a summary of the difference between the brains’ left and right hemispheres, taken from The Matter with Things.

So how might one characterise, as a whole, each hemisphere’s vision of reality?

One view, the left hemisphere view, is of a world composed of static, isolated, fragmentary elements that can be manipulated easily, are decontextualised, abstracted, detached, disembodied, mechanical, relatively uncomplicated by issues of beauty and morality (except in a consequentialist sense) and relatively untroubled by the complexity of empathy, emotion and human significance… This world is useful for purposes of manipulation, but is not a helpful guide to understanding the nature of what it encounters. Its use is local and for the short term.

In the other (the right hemisphere version), as in the world the map represents, and in the world revealed to us by physics, by poetry, and simply by the business of living, things are almost infinitely more complex. Nothing is clearly the same as anything else. All is flowing and changing, provisional, and complexly interconnected with everything else. Nothing is ever static, detached from our awareness of it, or disembodied; and everything needs to be understood in context, where, if it is not to be denatured, it must remain implicit… This world is truer to what is, but is harder to comprehend and to express in language, and less useful for practical issues that are local and short-term. On the other hand, for a broader or longer-term understanding the right hemisphere is essential.

The main junction of the two hemispheres, the corpus callosum, exists just as much to impede communication between the left and right as it does facilitate it. It is this dynamic, oppositional tension which gives the human mind its flexibility and richness of faculties.

Of particular interest for us here is McGilchrist’s treatment of schizophrenia in terms of hemisphere lateralization—namely in the usurping of the master by his emissary.

There are undoubtedly different qualities to the experience of schizophrenia and that of right hemisphere damage, and there is no simple equation to be made between the two (each of which having, in any case, a variety of manifestations). Nonetheless, it is striking how each and every aspect of the breakdown of reality in schizophrenia that we will now be dealing with is paralleled by what in a non-schizophrenic individual would indicate a recognised typically right hemisphere, not left hemisphere, deficit.

McGilchrist goes through many, many comparisons of the testimonies of schizophrenic patients with the observations of patients who have suffered strokes or lesions on the right-side of their brain.

Auspicious for us, McGilchrist also leaps into a very familiar domain to readers of this blog: modern literature, with his recommendation of the 1992 book Madness and Modernism by Louis Sass. McGilchrist writes

Might it be, then, that as a culture we were exemplifying [in Modernism] not, of course, a sudden epidemic of schizophrenia, but too heavy a reliance on the world as delivered to us by the left hemisphere, meanwhile dismissing what it is that the right hemisphere knows and could help us understand?

McLuhan’s expertise, of course, were the English Modernists and their French Symbolist predecessors. Sass covers this terrain in three parts, presenting it as the stages of schizophrenia at-large: “Early signs and precursors,” “Thought and Language,” and, finally, “Self and World in the Full-Blown Psychosis.”

In the conclusion, Sass summarizes

As we have seen, many schizophrenic patients tend to lose their sense of active and integrated intentionality. Instead of serving as a kind of anchoring center, the self may be dispersed outward, where it fragments into parts that float among the things of the world; even the most intimate thoughts and inclinations may appear to emanate from some external source or mysterious foreign soul, as if they were “the workings of another psyche.” But we also know that the self can come to seem preeminent and all-powerful: rather than drifting somewhere in space, like the detritus of some forgotten explosion, one’s own consciousness may seem poised at the epicenter of the universe—with all the strata of Being arrayed about it, as around some constituting solipsistic deity…

Thus, while a person suffering from schizophrenia is as likely to identify with God as with a machine, perhaps the most emblematic delusion of this illness is of being a sort of God machine, an all-seeing, all-constituting camera eye.

This machine self, Sass tells us, is largely a response to “reflexivity”, or what computer programmers and mathematicians call recursion. This is the nature of cyberspace, as I recently explained by analogy of audience-performer relations across the nesting of a recursive series of theater prosceniums. It is, more simply, the “Strange Loop” which Douglas Hofstadter not merely refers to recursion as, but personally identifies as. I grappled long enough with robot identities—but the topology of our world, and the incompatibility of being both a “view from nowhere” while also being an embodied person—Ernest Beckers’ “gods who shit”—is always the central crux.

“The war is in words and the wood is the world.”

The opening pages of Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore’s book War and Peace in the Global Village are, strangely, rotated 90°. Turning the book to compensate, the reader literally “animates” Charlie Chaplin riding to top a giant mechanical gear in a still-frame from the film Modern Times. The text then begins by explaining another curious facet of the book’s design.

The frequent marginal quotes from Finnegans Wake serve a variety of functions. James Joyce’s book is about the retribalization of the West and the West’s effect on the East:

The west shall shake the east awake…

while ye have the night for morn.Joyce’s title refers directly to the Orientalization of the West by electric technology and to the meeting of East and West. The Wake has many meanings, among them the simple fact that in recoursing all of the human pasts our age has the distinction of doing it in increasing wakefulness.

Joyce was probably the only man ever to discover that all social changes are the effect of new technologies (self-amputations of our own being) on the order of our sensory lives. It is the shift in this order, altering the images that we make of ourselves and our world, that guarentees that every major technical innovation will so disturb our inner lives that wars necessarily result as misbegotten efforts to recover the old images.

As we saw in my deeper analysis of McLuhan’s conception of metaphor, McLuhan’s idea of what he’d later recognize as the lateralization of the brain’s hemispheres was informed by poetry—especially the influence of Mandarin poetry on Ezra Pound. Lydia Liu criticizes McLuhan’s misapprehension of Chinese writing (on page 69!) of her 2010 book The Freudian Robot. He was working in the domain of Modernism, when romantic images of the exotic orient were blooming into vogue in the West. Later, of course, the Cold War and the Vietnam War also gave him irresistible opportunities for many more East-West generalizations of the sort which we would not broker today.

Make it make sense!

Fortunately for McLuhan’s posterity, the East-West dichotomy was only one of a million other ways he had of approaching the same universally-human thing. He had early considered this thing as the opposition of lone dialectic against the pair rhetoric and grammar, which continually re-composed the Western logos in classical Greek, Latin, and modern European vernacular languages. Wyndham Lewis before him described this thing as the static, arresting eye of the portrait artist (himself) vs. the infantile, Romantic, and easily brain-washed ear-for-music of the Bergsonian “time flux” and Gertrude Stein

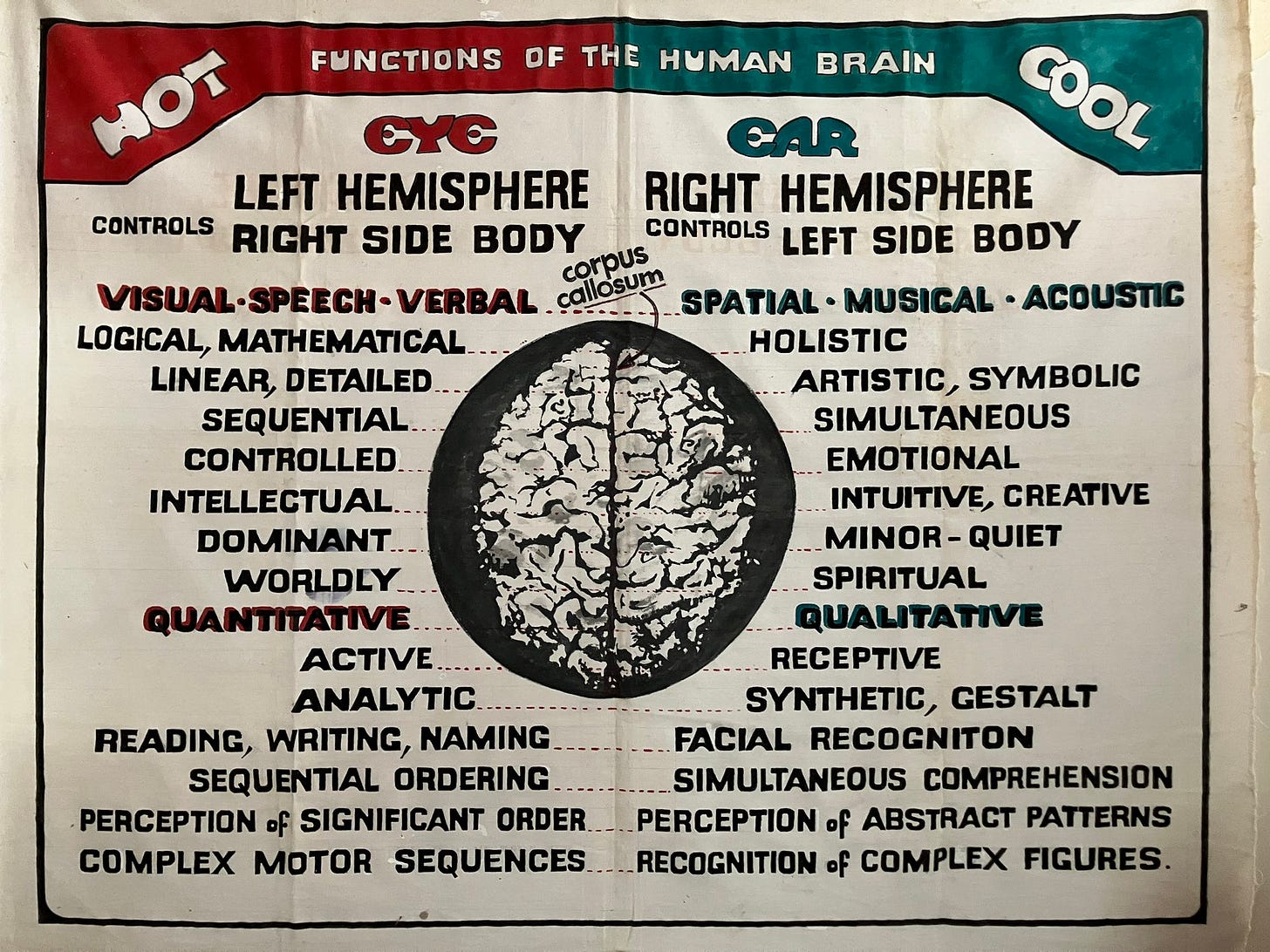

Most complex, of course, was McLuhan’s attempt to project these states of mind into the material environment. Specifically, in the various-ways which architects, urban planners, artists, and media-content producers create sensory-biased spaces or environments. His hot and cool classifications of aspects of the outer world were an attempt to complement the former descriptions of the inner faculties of eye and ear—to often confusing results.

It was only in 1976 that McLuhan came-late to integrating the lateralization of brain-hemispheres into his project (Check page 487 of Andrew Chrystall’s monumental The New American Vortex to read McLuhan’s excuse for his delay).

This adoption of brain-science was soon enshrined in a hand-painted wall poster hanging in his U of T coach-house.

If your eyebrow raises at the correspondence between eye and ear and left and right hemispheres, remember Lewis. McLuhan’s primary lens was art, and the means by which artists evoke the senses and crate spaces suitable to them—even transcending the sensory organ in question.

And so, between Louis Sass’s exploration of the relation between Modernism and schizophrenia, and Iain McGilchrist’s rehabilitation of the propriety of left-brain/right-brain generalizations, how can McLuhan advance the discussion?

Baseball is Culture

I’ve already written about the megalomania which my protracted psychosis inflicted, and I provided some of the strategies I employed to not imbibe too much of my own flavor-aid.

Sass, helpfully, provides clinical examples, which I can relate to, of the proportions of the psychosis which I had euphemized to Paul Levinson as “acoustic space.”

Many schizophrenics do seem to be highly preoccupied with experiences involving revelations of such cosmic or totalistic proportions… And, as schizophrenics disengage from the social and pragmatic world, any focused, practical concerns they may have had tend to be replaced by preoccupations of a highly abstract or universal nature. “Tell me what was on your mind,” prodded one interviewer. “Well, a little bit of everything, I guess,” responded the patient, “the present, the past, the future, everything I could think about.” One schizophrenic responded as follows to a Rorschach inkblot (Card #5): “The two ends look like the tail and rear end of something diving into something, diving into eternity, coming out of this world and going into nothing.

The preoccupation with general ontological or epistemological concerns, with issues pertaining to the nature of reality in general and to the general structure of self-world relations, is evident here; and it has resulted in speech unlikely to seem meaningful to the person not attuned to such issues. Statements like these seem to be attempts to express things whose intrinsic nature renders them close to ineffable, experiences that are so total as to pervade the whole universe, yet so subtle as to seem at times like nothing at all—experiences of such things as the being of Being or the unreality of Unreality, or, perhaps, of what it is like to feel oneself existing both inside one’s own mind and outside in the objects of one’s knowing.

Now, perhaps, is the time to revisit the good Dr. Ray. Gene Ray (who was, I’m sorry to tell you, never a doctor) was a prolific internet poster of the kinds of word salad which one finds in any collection of clinical case-studies of schizophrenia. He was, as I said, a schizoposter.

And what do schizoposters usually post? Totalizing theories of everything! Matters of great importance for the whole world.

Besides “the medium is the message,” which phrase is McLuhan most well known for?

“The global village.”

And life in the global village is the less-mad gestalt of everything.

Let’s bring this home, with helpful reference to McLuhan’s essay “Baseball is Culture,” printed in the October issues of The CBC Times, 1952.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Less Mad to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.