Seeking Attachment

Another Perspective in Developmental Psychology

The work of psychiatrist John Bowlby represents a different strain of developmental psychology than that following the work of Jean Piaget I’ve discussed here and on my main site. Bowlby’s attachment theory threw-off the early psychoanalytic emphasis on libidinal “energies” and “drives.” Instead, Bowlby said, when considering their behaviour, we out to consider how children and adults might recapitulate the relationship they have had to their caregivers in early life.

I’ve just finished a collection of his lectures, The Making and Breaking of Affectional Bonds, as an introduction to his work and have found a great deal of very useful common sense. It is the things we take for granted which we often leave unsaid, after all. And we must recognize that, often, what we take as obvious today often was not so apparent in the past.

After going through attachment theory, we’ll look at computers, life online, and modern sex culture through this lens.

Ambivalance and Tension

…the steps by which an infant or child progresses towards the regulation of his ambivalence are of critical import for the development of his personality. If he follows a favourable course, he will grow up not only aware of the existence within himself of contradictory impulses but able to direct and control them, and the anxiety and guilt which they engender…

I recently, in my quick look at the contemporary state of brain-hemisphere lateralization, talked about the importance of the regulation of opposing forces which occur throughout nature. All of the “order” which has arisen from the chaos of our universe was lifted by the balancing of great pressures in near-stalemate. The ocean is holding up the atmosphere after all, at nearly 15 pounds per square inch. And it is at the shore-line—that interface of great tension where land struggles against them both—where animal life first writhed and squirmed its way onto land.

All recent research in psychology and biology has demonstrated unmistakably that behavior, whether in other organisms or in man himself, is the resultant of an almost continuous conflict of interacting impulses: neither man as a species nor neurotic man as an afflicted sub-group has a monopoly of conflict. What characterizes the psychologically ill is their inability satisfactorily to regulate their conflicts.

That which is regular is ordered and under pressure. And the parent who a small child relies on is also an object of hate when they deny or frustrate that child’s desires.

Although our work will take a big step forward when theoretical issues are clearer, for many purposes I believe we can make good progress using such everyday concepts as love and hate, and the conflict—the inevitable conflict—which develops within us when they are directed towards one and the same person.

The primary catch for attachment theory is that the parent needs to remain stable and present for the child to persistently regulate against. Learning how to handle and integrate the emotional roller coaster of anger and fear and love and hate requires the consistent, reliable environment of the parent’s presence or, at least, ready accessibility.

What matters about the external environment is the extent to which the frustrations and other influences it imposes lead to the development of intrapsychic conflict of a form and intensity such that the immature psychic apparatus of the infant and young child cannot satisfactorily regulate it.

What happens when that presence is interrupted? When the familiar environment is changed? Here’s where Bowlby extends a familiar concept into new places.

Good Mourning

Bowlby and those he draws on and worked with spent a great deal of time and effort studying children who had been separated from their parents. World War II, and its aftermath, provided a lot of unfortunate circumstances where useful data could be gathered and observations made.

Since he was focusing specifically on the breaking of the attachment to the parent, the circumstance which lead to that breakdown was ambiguous. Whether they were alive or dead was a secondary consideration—they were absent. For that reason, Bowlby extends the notion of mourning into a psychological concept exceeding death, into the extended loss of someone to whom one was attached.

I was reminded here of something Alice Miller taught in her book The Drama of the Gifted Child about mourning the childhood one never had. Throughout the lectures in this book, Bowlby anticipates Miller’s advice to never frame one’s present as a return to the past.

All those who think in terms of dependency, orality, or symbiosis refer to the expression of attachment desires and behaviour by an adult as being the result of his having regressed to some state believed to be normal during infancy and childhood, often that of a suckling at his mother’s breast. This leads therapists to talk to a patient about ‘the child part of yourself ’ or ‘your baby need to be loved or fed’, and to refer to someone tearful after a bereavement as being in a state of regression. In my view all such statements are mistaken both for theoretical and for practical reasons.

Childhood is not to be discussed in order to be re-litigated per se—the re-evaluation and awareness one gets about one’s parents occurs in pursuit of understanding the present.

…it is not our job to determine who is to blame or for what. Instead, our task is to help a patient understand the extent to which he misperceives and misinterprets the doings of those he is fond of or might be fond of in the present day, and how, in consequence, he treats them in ways that have results of a kind he regrets or deplores.

How one is acting today may draw on that childhood. But since one is older now, one must come to understand one’s actions actions as those of an adult—not one’s childish self, but perhaps more like one’s own parents!

By construing them as childish and referring to them as such, a patient can easily interpret our remarks as disparaging and reminiscent of a disapproving parent who rejects a child seeking to be comforted and calls him ‘silly and babyish’. An alternative way of referring to a patient’s desires is to refer to his yearning to be loved and cared for which we all have but which in his case went underground when he was a child…

A second area of difference concerns how we suppose a person comes to apply to spouse and children, and sometimes also to therapist, certain disagreeable pressures, for example threats of suicide or subtle modes of inducing guilt. In the past, though the problem has been recognized, no great attention has been given to the possibility that the patient learned how to exert these pressures through having suffered them himself when a child and, consciously or unconsciously, is now copying his parent.

It is the process of mourning—which of course in common language refers to actual funerary rites following a death—where Bowlby sees the germs of healing. Here he enters into the realm of evolutionary psychology.

It is, therefore, in the interests of both individual safety and species reproduction that there should be strong bonds tying together the members of a family or of an extended family; and this requires that every separation, however brief, should be responded to by an immediate, automatic, and strong effort both to recover the family, especially the member to whom attachment is closest, and to discourage that member from going away again. For this reason, it is suggested, the inherited determinants of behaviour (often termed instinctual) have evolved in such a way that the standard responses to loss of loved persons are always urges first to recover them and then to scold them. If, however, the urges to recover and scold are automatic responses built into the organism, it follows that they will come into action in response to any and every loss and without discriminating between those that are really retrievable and those, statistically rare, that are not.

But when the attached figure is actually, irretrievably gone, then those instincts must play out regardless. The denial, the anger at abandonment, the frantic search or pleading will happen regardless. Bowlby examines a few case studies of people who suppressed those emotions, and thus maintained their grief in a subconscious way.

This and evidence from other cases suggests that, although immobilized, both his love and his anger had remained directed towards the recovery of his dead mother. Thus, locked in the service of a hopeless cause, they had been lost to the developing personality. With loss of mother had gone loss also of his feeling life.

Two common technical terms are in use to denote the processes at work: fixation and repression. Unconsciously the child remains fixated on his lost mother: his urges to recover and to reproach her, and the ambivalent emotions connected with them, have undergone repression. Another defensive process, closely related to and alternative to repression, can also occur following loss. This is ‘splitting of the ego’ (Freud 1938).

By becoming a new object of attachment by transference, a psychotherapist might become a new secure base by-which a person so-afflicted may resume and finish the process of morning.

Whether we are in the role of friend to a recently bereaved person or of therapist to someone who has suffered a bereavement many years ago and has failed in his mourning, it seems to be both unnecessary and unhelpful to cast ourselves in the role of a ‘representative of reality’: unnecessary because the bereaved is, in some part of himself, well aware that the world has changed; unhelpful because, by disregarding the world as one part of him still sees it, we alienate ourselves from him. Instead, our role should be that of companion and supporter, prepared to explore in our discussions all the hopes and wishes and dim unlikely possibilities that he still cherishes, together with all the regrets and the reproaches and the disappointments that afflict him.

This process, again, is not specific to death. It could just as easily apply to mourning the loss of attachment to a parent who is in jail or institution, traveling extensively, or has otherwise left one’s life.

What it is, precisely, which is lost in such a separation? Here is where things, for me, get implicitly media ecological! See if you can anticipate how.

Expedition and Release

Initially attachment behaviour is mediated by responses organized on fairly simple lines. From the end of the first year, it becomes mediated by increasingly sophisticated behavioural systems organized cybernetically and incorporating representational models of the environment and self. These systems are activated by certain conditions and terminated by others. Amongst activating conditions are strangeness, hunger, fatigue, and anything frightening. Terminating conditions include sight or sound of mother-figure and, especially, happy interaction with her. When attachment behaviour is strongly aroused, termination may require touching or clinging to her and/or being cuddled by her. Conversely, when mother-figure is present or her whereabouts well-known, a child ceases to show attachment behaviour and, instead, explores his environment.

Cycles of attachment and termination of attachment are how a child learns to regulate a feeling of independence and self-reliance in the world. Haidt has, of course, made a great many strides recently encouraging parents and schools to foster opportunities for voluntary terminating conditions on behalf of children.

There is now a mass of evidence to support the view that exploratory activity is of great importance in its own right, enabling a person or an animal to build up a coherent picture of environmental features which may at any time become of importance for survival. Children and other young creatures are notoriously curious and inquiring, which commonly leads them to move away from their attachment figure. In this sense exploratory behaviour is antithetical to attachment behaviour. In healthy individuals the two kinds of behaviour normally alternate.

Here is another of those tensions—attachment behavoiur and exploratory behaviour commencing with temporary termination of attachment. And note, when a child freely and confidently wanders away from their parents for a while, where is he or she going? To explore the environment! Bowlby defines the entire purpose attachment as such:

The person trusted, also known as an attachment figure (Bowlby 1969), can be considered as providing his (or her) companion with a secure base from which to operate.

What is the emotion to be regulated in the opposition of exploratory behavoiur to attachment?

Seen in this light anxiety over unwilling separation from an attachment figure resembles the anxiety that the general of an expeditionary force feels when communications with his base are cut or threatened.

Anxiety is the feeling of not having a secure base to return to. What a great metaphor! Attachment figures are a base from which one can depart for small reconnaissances and, from time to time, return. To reiterate:

…when mother is present or her whereabouts well-known and is willing to take part in friendly interchange, a child usually ceases to show attachment behaviour and, instead, explores his environment. In such a situation mother can be regarded as providing her child with a secure base from which to explore and to which he can return, especially should he become tired or frightened. Throughout the rest of a person’s life he is likely to show the same pattern of behaviour, moving away from those he loves for ever-increasing distances and lengths of time yet always maintaining contact and sooner or later returning. The base from which an adult operates is likely to be either his family of origin or else a new base which he has created for himself. Anyone who has no such base is rootless and intensely lonely.

And long experiences of such cycles of attachment and termination from such a base as the parent offers has a direct influence on

…the relative ability or inability of an individual, first, to recognize when another person is both trustworthy and willing to provide a base and, second, when recognized, to collaborate with that person in such a way that a mutually rewarding relationship is initiated and maintained…

A healthily functioning person is thus capable of exchanging roles when the situation changes. At one time he is providing a secure base from which his companion or companions can operate; at another he is glad to rely on one or another of his companions to provide him with just such a base in return.

There is a lot to be said about those two sentences. I will go into some modern sexual slang and analogies from AI history in just a moment, after we finish this little tour of Bowlby’s book of lectures. But let’s note here how neatly this concept of attachment provides a workable definition of the support one gives and gets in good friendship or companionship. To recognize another person’s reliability as an attachment figure is to judge how good a friend they might be. And what if you lack that discrimination?

By contrast, many forms of disturbed personality functioning reflect an individual’s impaired ability to recognize suitable and willing figures and/or an impaired ability to collaborate in rewarding relationships with any such figure when found. Such impairment can be of every degree and take many forms: they include anxious clinging, demands excessive or over-intense for age and situation, aloof non-committal, and defiant independence.

Notice the two opposing dispositions which might result from a failure to have had, or be able to make good attachments. The clinginess or need for constant affirmation may be obvious. But the second one I find more interesting (perhaps because more relatable?).

A pattern of attachment behaviour that is overtly the opposite of anxious attachment is one described by Parkes (1973) as that of compulsive self-reliance. So far from seeking the love and care of others a person who exhibits this pattern insists on keeping a stiff upper lip and doing everything for himself whatever the conditions. These people too are apt to crack under stress and to present with psychosomatic symptoms or depression.

Good friends are harder to find when you can’t be one yourself.

Everything is Media Ecology

Seymour Papert wrote a book in 1996 titled The Connected Family discussing how strange it is that responsible parents must reliably learn from their kids about how computers worked and how to use them.

He had testified a year prior as a witness with Alan Kay, the creator of the GUI, to the House Science & Educational Opportunities Committees in Washington against the interests of large tech companies and educational software firms. They likened the purchasing, with tax-payer money, of computers for every classroom as equivalent to putting a piano in every classroom and providing teachers two-weeks of music lessons!

Papert—Piaget’s protégé and the leader, with Marvin Minsky, of the second-wave of Artificial Intelligence development at MIT in the late’60s to early ‘70s—had spent decades teaching children how to program computers. He advises in The Connected Family against teaching children single-purpose programs—or, as we say today, how to use “apps.”

For the rest of his life, he worked on projects which created general purpose programming environments for kids. Later environments, like the MicroWorlds he discusses in The Connected Family, or like the Scratch language which Kay developed for the One Laptop Per Child project were all attempts to extend the viability of such an environment into the graphical, multimedia age.

For example, in this chapter I talk about using MicroWorlds to make a multimedia show. Most people who know software would think instead of using Hypercard for a simple project within the reach of children, and Hyperstudio or Macromedia Director to do a really professional job. I hope that as you become proficient you will want to try several ways to make a multimedia production. But at least four reasons contribute to my absolute certainty that the best starting point is a general-purpose programming system.

The first reason is a sine qua non: You get to the level of producing your first interesting effects as easily via this route as any other. The belief that rigid special-purpose software is “easier” has no serious foundation. The second is that what you will be learning will be useful in a large variety of other situations. The third is that at each point you will have a wider range of directions to go than you would with a special-purpose software. And finally, you will be in closer contact with the powerful ideas that undergird all computational tools.

Educational theorists spend a lot of time worrying about what they call the problem of transfer: If you learn something in one context, can you use it in another?

Papert rails against the proliferation of commercial software which promises its purchasers—parents and school-boards—effects which it needn’t actually deliver to children. And he exhorts parents to take part in, and learn alongside their children. And what they’re learning would be, in fact, fundamental and universal notions of computer programming that go back decades to the origins of computers as symbolic processors.

(In my long essay on Piaget and Papert, Cheating at Peekaboo Against a Bad Faith Adversary, I argue that Terry A. Davis, in his own schizophrenic way, felt called upon by god to continue this mission of Papert and Kay’s with TempleOS. It’s assuring to see corroboration across such a divide!)

The fact that Papert explicitly singles out both Apple’s Hypercard and Macromedia Director—the progenitor to Adobe Flash—as less desirable than a real, general-purpose programming environment is worth dwelling on. I’ve already talked about my relation to Hypercard, and how choosing it over Logo shaped my subsequent relation to computers. People my age grew up with Flash games on sites like Newgrounds and eBaum’s World. And we remember that age as liberated compared to the world of mobile games today.

Since Papert wrote this book, the socially-constructed prisons of “social media” and “smartphone” “app” stores have decimated the freedom of the internet. In turn, responsibility for what happens online has shifted entirely to those who have taken power over that online world—we exhort companies to do something, or politicians to regulate those companies.

The idea that parents and children, exploring the alien frontier of the internet, have the burden of responsibility for what happens is a very hard case to make. Because, by now, neither generation is in touch with computers as a computer, and neither can use their experience as a base for the other to take off-from—except for the lowest-common denominator of social media apps.

And the tragic, worst-case-scenario of the OLPC project has only exacerbated the problem by creating a global market demand for Chromebooks—the absolutely worst sort of computer one could have if one desired to understand what computers were.

Microworlds

We were talking about Bowlby and attachment theory, right? I promise, we’re still on track here!

There were two schools of AI development since the fields founding in the ‘50s. Papert and Marvin Minsky were in the symbolic processing school. This school opposed the neural networking school which is today ascendant in tools like ChatGPT and the like.

This first school was founded on the work of Herbert Simon and Allen Newall, who conceptualized a general model of intelligence as a symbol machine. In the 10th Annual Turing Speech, they explained

The first step of the chain, authored by Turing, is theoretically motivated, but the others all have deep empirical roots. We have been led by the evolution of the computer itself. The stored program principle arose out of the experience with Eniac. List-processing arose out of the attempt to construct intelligent programs. It took its cue from the emergence of random access memories, which provided a clear physical realization of a designating symbol in the address. LISP arose out of the evolving experience with list-processing.

According to Hubert Dreyfus (namesake to Professor Hubert Farnsworth from Futurama), the symbolic processing school of AI sought to keep intelligence rational within the Western philosophical tradition. Such AIs functioned according to rules and encodable knowledge, and could be understood. The neural-network school, by contrast, created unknowable, black-box AIs which could only be trained via input-and-output, analogous to the psychological school known as behaviorism founded by B.F. Skinner.

Papert, drawing on Piaget, developed the idea of the “microworld” in 1970 in order to frame and model the development of symbol-based intelligence from simple to complex. Papert’s Logo was a variant of LISP. The Logo environment, like the MicroWorlds environment, and the environment of Scratch, (and the environment of EMACS, for that matter), were microworlds. They are rule-based domains which one can grow in and master, learning transferable skills. Upon mastering enough universal rules in multiple microworlds, a child may transcend them to a higher stage of development.

Dreyfus criticized this view of development heavily. The larger world we live in is not a summing of microworlds. It is not reducible to a common set of rules or laws, and the philosophical search for such universal laws, especially since the European Enlightenment, has lasted centuries to no avail.

I think Dreyfus’s remarks make sense given the lofty ambition of creating sentient life in a machine. But as a pedagogical tool, Papert’s approach is far preferable, for three reasons:

1. Human Culture has Norms

There is a limited amount of things we can learn as mortals. And, more-so, of all those things, most people will learn mostly the same thing. This is, roughly speaking, the nature of culture. The reasons we do specific things are, roughly, justifiable or challengable according to rules or rationality. And certain things which one may learn in one domain are transferable to others. There are building blocks which are good enough—even if someone like Wittgenstein or Heidegger will drive themselves crazy about how imperfect they may be after all.

2. Computers are Environments

If parents need to present a secure base for children to take expeditions from, then the the child needs to be able to actually return to the parent and discuss what they find. The common lingua-franca of computers was laid out by Simon and Newall half-a-century ago. Everything we do on computers today is an elaboration on what LISP can do. Alan Kay called LISP “the single greatest programming language ever devised,” and justifies this claim by comparing it to Newton’s formulation of physics.

When I talked about the relation of myself to others, I emphasized the importance of a common perspective on our environment. I wrote

At work, and at the local bars, I was doing serious anthropology. I was probing, watching, and paying attention to everybody else’s relation to the world. What they paid attention to, how they dealt with it. What they ignored and took for granted. Especially regarding computers, of course, but also socially.

I was forming attachments to new people by coming to develop a common base with them for our shared exploration. This is attachment theory.

If generations are going to grow up in a common computerized environment where they have a rational lingua franca, it should be somehow reducible or traceable to computers as such a medium. The history of the medium must be its base. The fact that cyberspace presents a fractured world full of strangers to which parents increasingly abandon children to become alien is, certainly presents circumstances which terminate attachment. I grew up unable to talk to my parents about what I was doing online—they had no frame of reference.

Today the situation is far worse. Each special-purpose “app” is different from the last. Without access to source, there is no ability to get to the ground of what’s going on.

I see the world (or microworld, if you like) of Free Software as the most mature and viable common-ground for regrouping culture, should culture ever recognize the need to escape this trap.

3. We are attached to our computers

As Sherry Turkle (who was, incidentally, married to Seymour Papert for several years) has made it her career to point out, we form attachments to our computers. We project parts of our selves into them.

Let’s explore this by way of a story of the evolving psychology behind office computers.

When the computer software landscape shift abruptly, there is a great business opportunity for “retraining” employees. The first major disruption was the need to retrain millions of typewriter users on word-processing software—I touch on that story in my Cheating at Peekaboo essay. Cogent here is how the IBM team in charge of killing-off market-demand for the company’s Selectric line saw the solution in video-games.

The notion of play and exploration from a secure base standards allows computers to be easy to use, and features to be “discoverable” without exhorting users to read manuals.

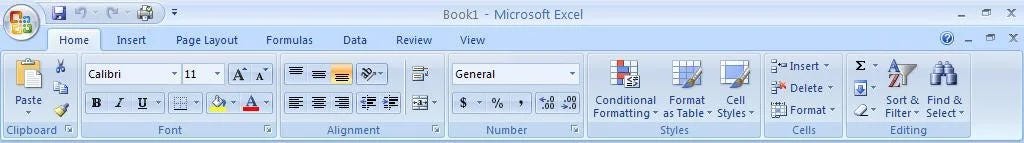

The Common User Access (CUA) schema was IBM’s next move into making their computers easier to use. In truth, they had to catch up with Apple. Jointly with Microsoft, they developed the UI-paradigm which reined in desktop computers for twenty years—that of standard pull-down menus and short-cut keys and drag-and-droppable icons.

Windows 95 was perhaps the widest debut of the CUA standards, although they had been unevenly implemented across different programs in rudimentary form for a decade prior. CUA standardization is what allowed children to dazzle their parents by exhibiting competency in programs they had never before seen: most programs used the same menus, shortcuts and other interface tricks.

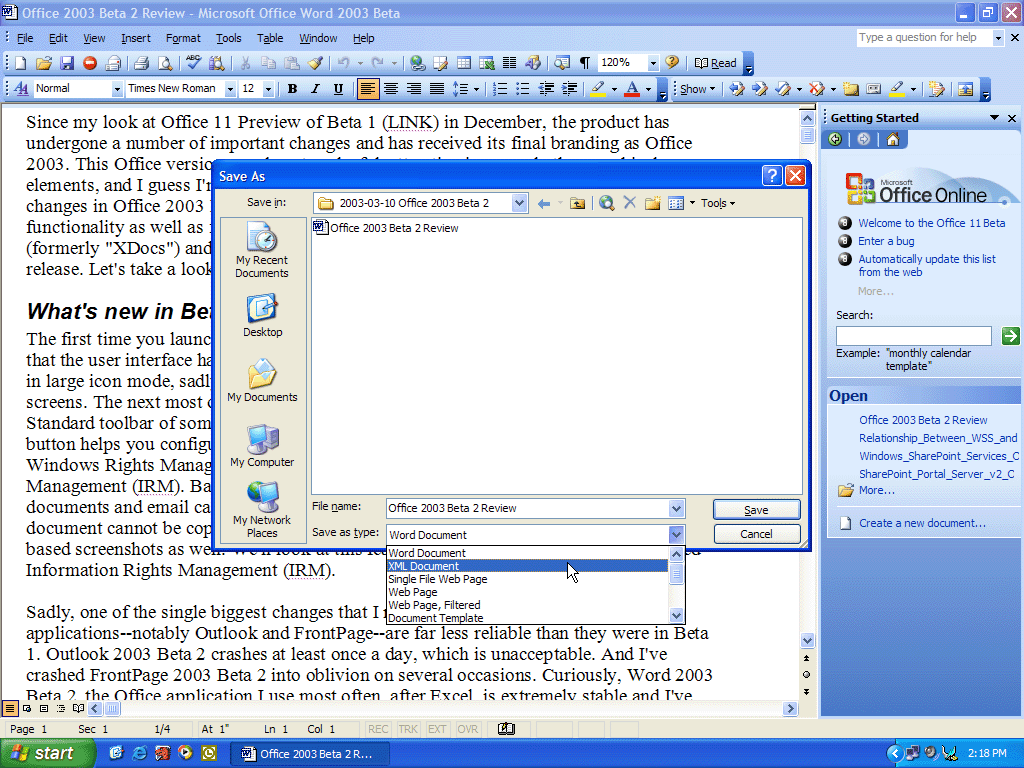

The last familiar instantiation of CUA for office workers was Microsoft Office 2003.

After that, Microsoft changed the game. Instead of straight-forward, easy-to-master user interface with sensibly organized options, they created a nightmarish maze of options which would take months to learn. Months which, once invested, would lead to feelings of mastery of a micro-world which users would never want to leave.

The loss of decades of familiarity with CUA standards represented a termination of attachment to the old way. Habituation to the new environment would go one way. And from then on, software developers knew that loyalty to an app meant making that app unique.

Decades of standardization has been undone. CUA wasn’t even a standardization which Papert supported—he supported actual programming as the standard. But CUA was, at least, still an interface “language” which held programs in common. Worse, the remote server-side—or “cloud”—nature of apps allows companies to sever attachment whenever they like. They can hold is a threat, even—like Bowlby’s allusion to parents threatening suicide to coerce their children.

Where does that leave us?

In Life on the Screen, Sherry Turkle designates the knowable age of machines—that of symbolic processors and readable, programmable code of rules and logic—as a modernist age in abatement. She writes in 1994 and, furthermore, she works as a translator of MIT jargon into plain-English for the larger, less tech-saavy world outside. But this role of translator unfortunately obscures the fact that MIT was not the only place where “hackers” existed. Her omission of Free Software from the saga is understandable, but tragic.

While she observes the fragmented psychological state resulting from our fractured software landscape, she makes no recourse, as Papert did, to any solutions or ammelioration of the problem. It is, frankly, not her job as a scientist to prescribe, but to describe. She observes in the ‘90s what happens when kids use commercial software, just as how in her first computer-centered book, she observed what happens when kids used Logo in the ‘80s. The changes in that decade are precisely the collapse of programming as a meaningful part of computing for most people.

I argue, and continue to argue, that this has everything to do with developmental psychology. How can we explore our environments when our environments are inscrutable? How can we form attachments when we exist in different environments? When the space our physical bodies share is mediated by-and-through the space on a screen to which we’ve surrenderd control to plainly-hostile entities?

Which one of you is the secure base and which is the dependant exploratory party? 😈

Papert talks a lot in The Connected Family about radical the changes will be when anybody can learn anything they want on demand. Relationships and sex is certainly a main topic—and has formalized into a coherent system.

If the projection of our identities in cyberspace has reduced the body to it’s mere expressive art-piece, it has also left it an object of sensual pleasure. Maybe this says more about me, and who I select for as friends, than it does the culture I’m trying to nail-down here. But when I read this quote from Bowlby:

A healthily functioning person is thus capable of exchanging roles when the situation changes. At one time he is providing a secure base from which his companion or companions can operate; at another he is glad to rely on one or another of his companions to provide him with just such a base in return.

I immediately thought “switch.” As in, I’ve heard different friends of mine, on more than one occasional, talk about relationships in terms of “dom” and “sub” in a way nearly-perfectly amenable to attachment theory. Oppositional tension, attachment, and temporary termination of attachment can be fun.

There is always a non-expert language of pop-psychology in currency—the one most evident today is thereputic in tone. Poeple often “self-diagnose” with terms stolen from the DSM, etc. But when I read Bowlby’s book, analogies from sex culture kept popping up. In one way, it makes sense—adult “attachments” are primarly about intimate relationships.

But is it possible, if sexual language continues to seep into pop-psychology, that a confusion of super-set and sub-set might be instantiated? The niche langauge of “dom” and “sub” are surely a particular instantiation of the universal of attachment.

What the unaugmented body is good for is less and less nowadays—and sex has amplified in course to fill the void. In future posts, I’ll carefully wade deeper into the ramifications of these disproportions and how it is that yesteryear’s psychological metaphors may be taking root within this amplified domain.

Parents, like media, create familiar environments we act within and from, be they healthy or not. And we do become ‘attached’ to both as the place we must return to after exploration, ‘home’ so to speak. Too dramatic a shift in either undermines identity, our relation to the environment, and creates distress, ‘loss of identity’.