Life in the Cave

Once I got high-speed internet as a teenager, I thought the rest of my life had finally arrived.

The hundreds of hours I had spent pouring over the spines of cassettes at the Super Video 99, looking for some delectable je ne sais quoi to make my afternoon, were only a preparation. Now, with broadband, I had an unlimited pipe to a century’s worth of cinema and television from across the world—more than I could watch in a lifetime.

Aware of my mortality, I styled my quiet, humble acceptance of the impossibility of watching everything-ever-made as a show of the highest maturity.

I spent a decade stoned out of my mind and culturally-enriched to a degree of both breadth and myopia never-before-possible in human history.

Eventually, I stagnated. I, myself, the person in control of the scene before me, was neither changing nor growing. It was, rather, the environment around me which was changing (into an undifferentiated clutter of forgotten and neglected objects) and growing (in technical complexity and cave-like darkness). A bigger, broader library of films, miniseries, television programs, and prog-rock albums amassed. My computer monitor and the number of speakers in my surround-sound setup grew each year. So did the number of creative places to balance styrofoam take-out containers.

I’d not like to dwell on this any longer than this. But I share now this short, uneventful and immemorable vignette of ten-year’s duration because it stands as my most relatable experience to the topic of our next few posts.

The Homunculus

Everyone steeped in internet rationalism and/or cognitive science is familiar with the homunculus fallacy. In its simplest form, it’s the mistake of trying to explain how the brain works by appeal to a little “you” inside of your head.

The classic example is an “explanation” of visual processing in which an image is recorded by the retina, conveyed by the optic nerve, and then transmitted by the visual cortex to the rest of the brain, which “sees” everything. While it is true that images are recorded by the retina and conveyed to the rest of the brain by the optic nerve, this does not explain how the brain processes visual data. Instead, one imagines something like a little person or a floating consciousness (the “homunculus”) who does the real work.

This position is typically refuted by arguing that this requires an infinite recursion.

The reason nothing can be explained by a “you” inside your head is because that “you” would need a deeper “you” inside its head, and so on, forever. What the homunculus is, then, is a conceptual black box; a wrapper for the mystery you are only pretending to solve.

If, for instance, you argue that an optical illusion tricks “your brain” into showing “you” something that’s not real, you’ve committed the fallacy: your brain does not precede “you” in some linear chain. Your brain doesn’t interpret sense data first, and then pass it along to “you.”

Your optic nerves precede the deeper levels of your brain, you might argue. But now you’re disowning your own eyes by preserving only your brain alone as “you.” That again leaves “you” a disembodied black box dwelling inside your skull. Not only that, but a disembodied black-box inside your skull that has its own sense of vision to be tricked. A sense of vision separate from your fallible eyes and optic nerves. A sort of brain-vision that might have avoided being tricked if it could bypass your fallible human eyes and optic nerves, and see reality directly for itself, with its own non-existent “eyes.”

Since we will soon build on an inversion of this idea of the homunculus, it will be worth fleshing it out a little more.

Alchemy and Brain Science

Homunculus is Latin for “little man,” and the notion dates back to very old ideas from alchemy about the power of science over creating life.

This image resonates, for me, with ideas of mystic power and the scientific megalomania of Dr. Frankenstein and Faust. Power over life and voodoo dolls and, today, designer AI lovers and social engineering and, generally speaking, any instances of the grooming of anyone enthralled in total power-disparity.

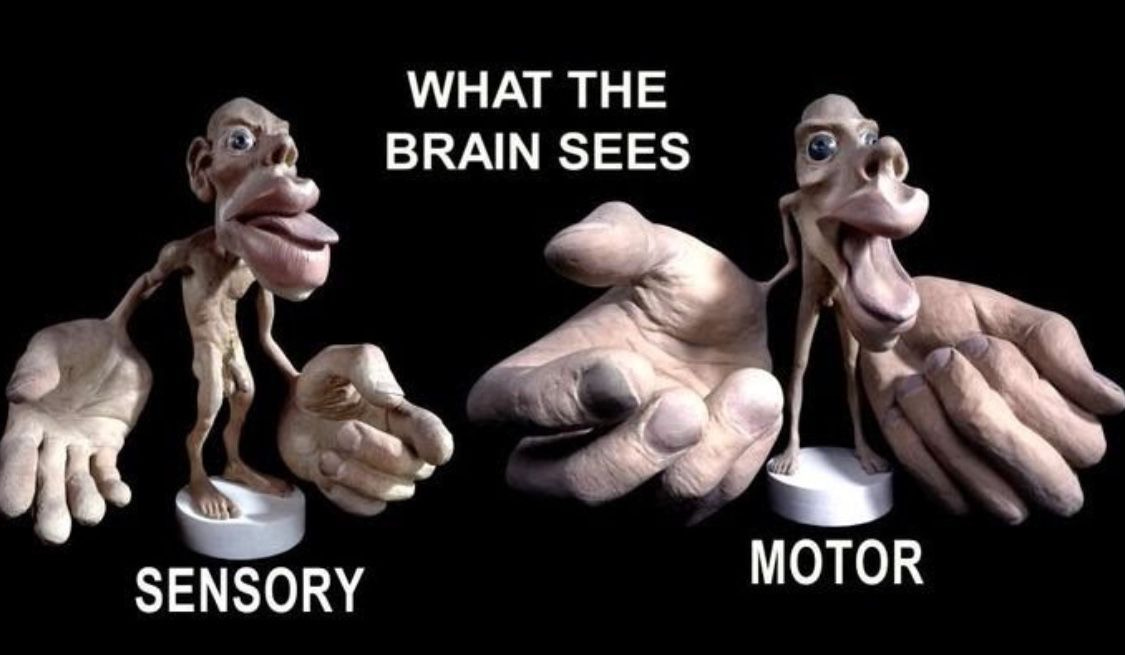

Besides the recursive philosophical example given in the preceding subsection, science also uses the analogy of the homunculus in demonstrating where all the nerve-endings on your body end up leading to in your brain. That is, the map of your body outside-in. This actual “little you” inside your head is not an infinite recursion, it’s a material fact of animal biology.

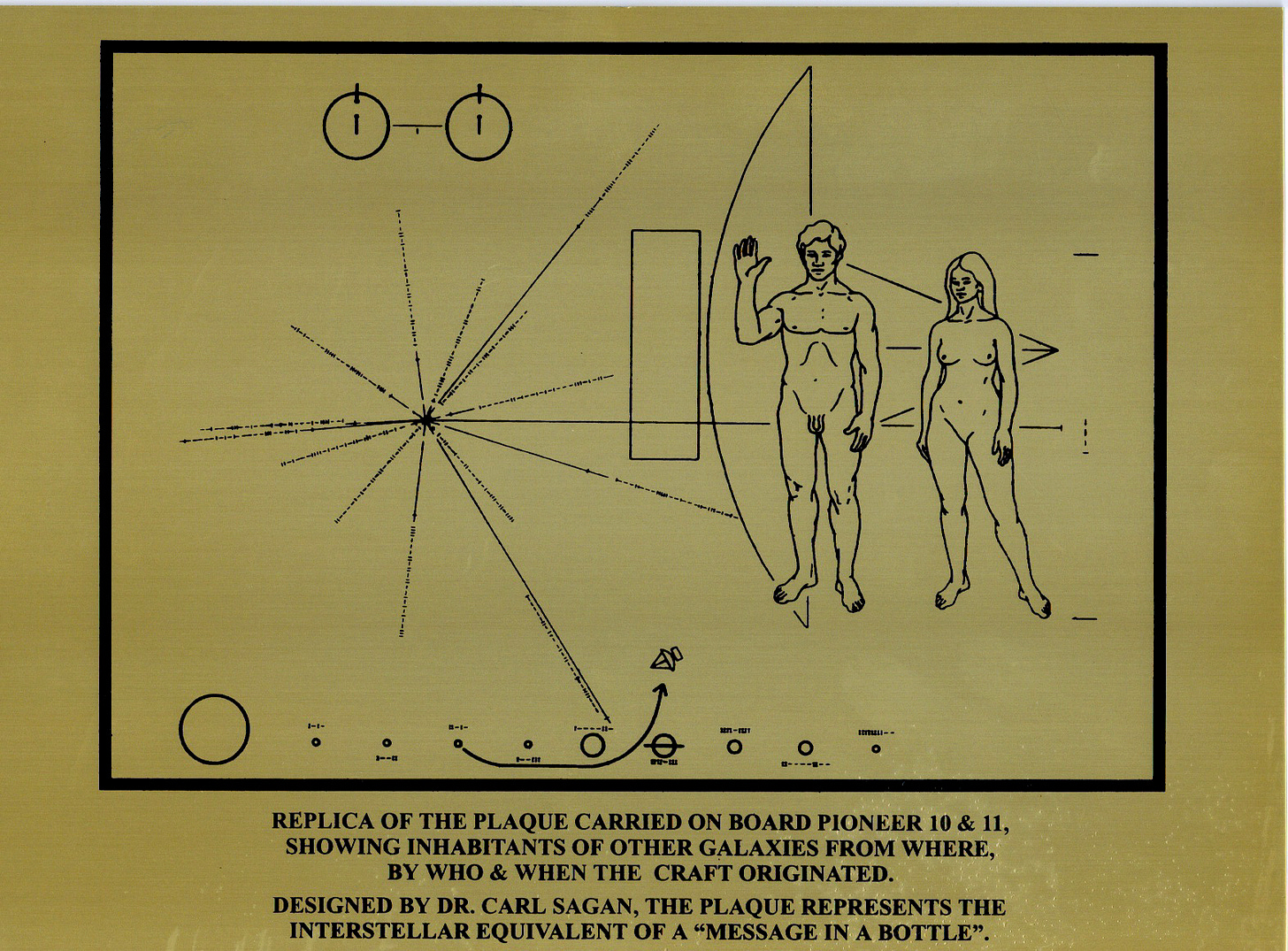

From the outside, humans take on the familiar proportions of Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, or Carl Sagan’s plaque on the first NASA probes to achieve escape velocity from the Solar system.

But, adapting the proportions in the homunculi above, we can see that in our inner space—at the other end of our nerve endings—our bodies take on much different proportions.

You’re all face and hands!

And, of course, that makes sense. Babies put everything in their mouths to feel them before they start learning how to grasp, hold, and manipulate objects more minutely. And noticing anomalous objects in your chewed-up food is a very useful survival mechanism. Hands, and opposable thumbs in particular, are essential for tool usage, and humans have often been defined as “tool-creating animals.”

The Edge of Us

I bring in all these different conceptions of the self as inner-homunculus to set-up its inversion.

Cognitive scientists have stressed, over and over, that we are embodied. That we are not living inside of our heads, but rather that we live through the agency of our bodies within our environment. But such a thing cannot be merely asserted by proposition.

It is an inescapable feeling for most of us that who “we” are is not only what the appearances of our bodies, or even our actions, convey. That there is more to us than merely what you see.

Most of the time, we project that more-of-us inside ourselves. We navel gaze. We close our eyes and live enter into the richness of imagination in both waking fantasy and nights dreams. The “true self” is within, larger than life. When we open them again, we find who we seem to be wildly lacking.

As I’ve elaborated in many different places, I suspect the development of this gap is always catalyzed, if not completely maintained, by media. But it is developed. Which means over time.

No amount of propositional, logical reasoning about who I am my body can counteract the years of habituation to the world which shaped me into feeling I am not.

In my recent talk with developmental psychologist J.D. Haltigan, we discussed the precarious nature of of trying to become one’s internet-identity in the real world. The result is, he argues, often behaviour which has been traditionally identified as clinically pathological. Mentally unwell. Our talk lead us to the overarching question: how do we find and normalize a healthy form of development into “the real world” for young-people who grew up on the internet? It’s a tough question, especially since I think the issue goes as deep as even object permanence.

Yet it’s an important question, because what we’re doing now is not cutting it. Just as incessantly asserting “you are your body!” to someone who has had a lifetime of developing a contrary phenomenological sensation is futile, I’ll argue that socially becoming who one really is (whatever that means) by raw, heavy-handed assertion and irrepressible and shameless public performance carries a similar measure of futility. You cannot just be whoever you say you are, even if you walk the talk, if the stage itself (let alone the audience!) does not support you.

This conversation is, naturally, extremely sensitive. A lack of care in discussing such matters easily collapses into bitter contention and tribalism. There is, however, a way forward if we pull the picture of “our real selves” inside out. If we invert the homunculus.

Insofar as our senses fill us with perceptions of what may be going on in the outside world, I’d like to think of our inner-sense of self as being that which we are filled with from without. Not in the overly abstracted, 20th century language or reified media-content. That is, cultural symbols or myths or archetypes or stories or avatars or the rest of that clichéd, cybernetics-age dreck of floating signifiers in the platonic realm of information.

Rather, I’d like to but in the sense of, first, how we extend our selves into the the environment and, second, the reciprocal action of becoming what we and others have beheld of those extensions of self. I’d like to do so as methodically and materially. And by resisting the implicit deference to formalized theories, concepts, abstract “frames,” and other print-oriented abstractions as I can.

There are many ways in which we extend ourselves into the outside world—and new ways of doing so are innovated with each technological speed-up. Any event that we can assume direct causal responsibility for is implies a physical extension of our agency into the outside world. For most of our evolution, our actions couldn’t exceed the reach of how far we could throw a rock, or bellow a loud cry.

We will start with this human scale today, and in several more upcoming posts, we will explore technical forms of our extensions and how they relate to personal transformation or stagnation; to self-control or to surrender of agency and personhood to external forces.

I believe the earliest expression of our selves, in their fullest sense, into the outer world was social. It was our reputation. Our reputatoin is simply who we are said to be when we are not ourselves present. It is who we are known to be. When it is accurate, our reputation is who we can be reliably be predicated to be. And, ultimately, our reputation is who we will be remembered to have been when we’ve passed away.

What’s in a Reputation?

Machinery is aggressive. The weaver becomes a web, the machinist a machine. If you do not use the tools, they use you. All tools are in one sense edge-tools, and dangerous. A man builds a fine house; and now he has a master, and a task for life: he is to furnish, watch, show it, and keep it in repair, the rest of his days. A man has a reputation, and is no longer free, but must respect that. A man makes a picture or a book, and, if it succeeds, ‘t is often the worse for him.—Ralph Waldo Emerson

We all agree that we have some control over what people say about us—we all hope that our best selves are noticed, and what we will be remembered by. We all fear the shame of our failings becoming the subject of discussion.

Celebrities, politicians, and other public figures spend a great amount of effort and money managing their “image.” But I’ve a future post drafted to handle these technological amplifications—for now I’d like to just deal with the age-old, human-scale reputation of natural word of mouth.

Christianity hinges on the mutual forgiveness of sins and subsequent alleviation of the torment of their endless recollection. People often reinvent themselves in rituals of new-beginnings, or run from their pasts to new cities in attempts to slough-off reputation’s burden.

Some people with a deficit of self-awareness have no idea what their reputation is. I often felt that way when I was younger. I had a nagging feeling that everyone around me was too “nice” or “polite” to tell me just exactly what it was I was missing. We might term this a “Sensitive Canadian” problem. I’d regularly hear friends and family talk about other people, to the betterment or worsening of their reputation, but it was hopeless for me to even imagine with what tone anyone might be speak about me.

It was like I was walking around in a tiny society-altering bubble which made people stop speaking honestly whenever they got close to me. It’s like they sensed I couldn’t handle it. And they must have been right, because I lacked the nerve to even desire to eavesdrop on how people acted or spoke when they thought I wasn’t watching or listening. I couldn’t harbour even a dim flicker of curiosity about my reputation from the gale of fear which even the possibility of finding-out stirred-up!

I am speaking somewhat rhetorically. But to continue this reductionist, exaggerated case study of “me” in the terms presented in our opening vignette: all my learning and merit was in my vast and trivial knowledge about obscure cinema and music. And this vast trivial knowledge, the result of a great investment of time and opportunity-loss, was inconveniently of a value which few others would recognize as meritorious enough to acknowledge with the seriousness which I felt was due.

I had all this great taste, but nobody else could see it. This is the closest I got to wishing someone would see “the real me.”

In retrospect, there was also a whole series of tests which such a hypothetical observer would need to pass in order for me to take their recognition seriously. So many tests, in fact, that such an observer’s existence was rendered impossible.

Of course, they’d need to not be merely trying to endear me to them or otherwise be condescending or faking it—they’d actually have to know the subject-matter as well as I did to have earned the right to their opinion.

At the same time, they’d have to not embody any of the traits about myself which I did not like. They’d have to, actually, be the opposite of me in as many ways as possible, because if I could project my own self-loathing onto them then I’d necessarily reject their praise of me as their own projection. They wished they were me! Ha! How pathetic!

My solitary, solipsistic identity was a self-defeating construct. And my careful, strategic evasion of the painful self-awareness which would have lead to its collapse did nothing to prevent its eventual collapse anyway.

We all grow up

Things have improved immeasurably in the intervening years, lessons from which are the subject of this blog/newsletter.

Nowadays, people generally let me know pretty quickly what they think of me in a way I had never experienced in my first thirty years. I’ve got a reputation—and while it’s pretty weird, it doesn’t seem to be a particularly bad one.

But what’s most important to me, personally, is that I know my reputation exists. It’s tangible. I regularly encounter its effects. While I all-too-frequently don’t enjoy these encounters, it often feels like a phenomenological miracle after so long-living in the dark about myself.

It’s the answer to a question I had been asking years ago: what’s the difference between individuation and alienation? The alienated can’t accurately proportion themselves to, and evaluate themselves by, their reputation. Regardless of the reputations accuracy—they can’t understand it either way. You need to be socialized to close that loop. Even if not of this world, you still need to be in it.

Reputation is not something anyone can see the whole of. And I don’t want to anyway! I’ve too much humility... or pride... or some virtue (I hope) to go pull some reality-television stunt in a fake nose and moustache and go about asking my friends and family what they think of me. For the love of God never put me in some damned This Is Your Life spectacle—I’d walk out. (An open-casket funeral might carry the same risk!)

Social Media—the old kind

I generally only watch films or television socially now. People generally know that I like to be invited to watch movies as a social gathering—I know that because it happens semi-regularly. I usually spot all sorts of obscure references and in-jokes, and think I’m more tactful in my commentary than I used to be.

But I’ve abandoned solitary movie watching as near-totally as I can. Happens once or twice a year maybe. And instead of walking everywhere with headphones glued to my skull, I generally only put on music to listen to while I cook or clean, or sometimes to jam-out to on the late-bus home from a night out. I’m ashamed of the years wasted living in my own cave. A social life starts begins the exposed and open senses.

That doesn’t mean, however, that those years are any less a part of me. Who I was for then is still a core trait of my identity today—it’s how I learned to express those facets which has changed.

What I remember from the vast glut of media content I’ve consumed provides me a lot of good material for discussion with people from all walks of life. Most usually I bring it up as a gentle pivot away from conversations about all the contemporary programming that I’m not watching.

Someone says they really like Ari Aster, and I’ve only seen one of his films so I say, “His stuff is kinda reminiscent of The Wicker Man, eh?” and they say, “What, the Nicholas Cage film?” and I say, “No, the original! From the ‘70s! It’s all explicitly pagan and shit,” and they go, “Oh! I have to see that!”

I live in this funny mirror universe where nothing I could recommend is licensed for viewing on Netflix or Amazon Prime or Disney+ or Spotify. The open-society of video store cassettes has fallen to the gilded cage of limited, rotating IP. So nobody talking to me about contemporary shows can do-so without me pivoting to some old thing they’ve never heard of and can’t see. Lots of conversations fizzle out with the mutual-exchange of recommendations that both of us know we are unlikely to ever actually watch.

But those rare moments when we do find an obscure point of common familiarity—some show they saw once as a kid on television that they never thought anybody else had ever seen—the floodgates burst open, and the talk can go on all night.

The Medium

Furthermore, a love of cinema like that which I had had can’t help but lead to a faculty for dramatic critical analysis. I’ve seen enough films, both formulaic and experimental, to recognize film forms when they play out in my social world. And I grapple with questions about how I might go representing aspects of waking life within the film-form. “Could I make a movie about this? Has anyone managed to capture this on screen?” are technical questions I frequently ask myself. More frequent are the questions are regarding reputational risk. “Even if I could capture this in film, could I make a movie about this without getting completely skewered or black-listed? Could I make a movie about this without enraging everyone? Could who I am survive being the guy who made the movie about this? Would it be worth it?”

And I often notice when people seem to be projecting old film archetypes onto new, totally changed environments or situations. Nerds today are not the ones bullied by jocks in Revenge of the Nerds. And they’ve long changed from the lovable, pedantic weirdos from Kevin Smith’s ‘90s films like Mallrats.

I’m sure we have all experienced a suspicion that someone is describing their contemporary lived-experience in the setting of an anachronistic, self-serving nostalgia. I’m pretty sure all of Big Bang Theory existed in this unreal dimension—and I don’t only say this because people often told me I remind them of Sheldon Cooper. 😮💨

My intermittent sense of social acuity is built, I think, on this background in cinema and television. When I do get people, I can talk about it in very concrete terms—like I’m analyzing a film. And I think the temporal dimension of having watched so many older films is the most important part—I can come at the present from a sense of the past. Not necessarily the past as represented in films, but the implicit past, even, of how the films were made. How audiences must have been, back then, to have been able to enjoy or dislike such a film then, as compared to now.

Next Time

How media shapes people—beginning with myself—is radiant in their very behaviour when you train yourself to understand the media itself. That is why, in our next examination of the larger self in our inversion of the homunculus, we’ll get into the more technical extensions of self.

We’ll also have a chance to deeper investigate the complex interrelation between personal stagnation and environmental change.

really lovely, thoughtful piece. thank you.