Remember when our devices were discrete? Even when everything became computerized, our gadgets were single purpose. You had a phone, you had a digital camera, you had an .mp3 player, your Palm device was just a calendar and notepad. If there was a mediating technology which glued them all together, it was your desktop or laptop computer. Its unifying ground was its file-system full of media files and, mirroring our single-purpose gadgets, the single-purpose applications you used to manipulate those files.

For many of us it still is this way; for many newer generations of gadget “owners” it is not. I put “owners” in scare-quotes because people who don’t control their devices can hardly be said to be owning them. Quite the contrary.

There is a central insight in this convergence of devices to be abstracted and made practical today. I say abstracted because I’m not merely going to recommend just going backward and carrying a digital camera and an old iPod around in your purse. Rather, I’m thinking only about the centrality of you and your computer’s file-system in the old-way of things. That centrality, compared to the peripheral nature of each device, is the key to addressing some of the most dreadful anxieties which long-kept me from being Less Mad.

The Architect

These posts are coming at you out of order—sorry, that’s just the creative process. So I might have to retitle this as “Part III” of my homonculus series later, we’ll see. If this were a book I’d do it properly, but I owe you regular serialized posts, so you get it in the order I can write it. Soon you’ll hear about my concept of the stagnant homunculus: my observations of how life-changes and goals which actually rejuvenate some people and lead to growth can be differentiated from those which only waste everybody’s time, money, and personal-reservoirs of encouragement and hope.

For now, I’ll tell you that the primary difference between real change and bullshit change is the role of sustained personal agency involved. For over a decade, I’ve mused over the location of my hypothetical “locus of agency”—here’s an old Reddit-post of mine on the TLP sub which uses the concept in terms of McLuhan’s “Narcissus as Narcosis” probe from Understanding Media. Is the larger ecological system comprising my “choice architecture” (to use the contemporary euphamism for behaviourist Skinner-boxes) on-top of me? Or am I on top of it?

If you’ve read any modern books of contemporary, scientifically-derived motivational psychology or behavioral economics or commercial “app” “UX” design, you understand my lament for the “meat robot” conception of the human individual. We are, so-far as the larger system is concerned, comfort-seeking puppets of stimuli. I’ve furiously grappled the notion for so long that I’m now married to it—such is the nature of all passionate relations.

That puts me in the role to turn it on its head. Okay, fine, my free-will can be considered to operate within the confines of flow-chart of choices. Great. I’m a programmable meat-robot. Fine. I’m more than that, but at least I’m largely that too. Going back to my explorations of Robert Kegan’s developmental psych, I am not a meat robot, I have robotic qualities within my meat.

So who decides what my choice-architecture is? Who’s doing the programming? Who is the architect? Is it possible for me to wrestle some control back from him over my own design? How can I trust myself to that sustainably? In a way which lasts the years and years necessary for me to develop a stable attachment to it? In a way resilient against capture by commercial or ideological or self-destructive designs from without?

Air-Gapped Agency

In computer security, the most secure machine is the computer which is not connected to a computer network. It is said to be “air-gapped.” Its security is 100% (okay, well I mean EMPs and Faraday cages and attacks on the power-grid and thefts of its off-site backups aside) physical. How well-locked is the door to the room it is in?

We’ve a long, long history of securing physical space. And we’ve a mere half-century of so-called “cybersecurity”—and look at how that’s going!

In the early years of recovery from my psychotic break, my small collection of Palm devices became something of a fetish-object for me. That is, I tried over-and-over to use it to fill a hole or absence in my life into which it no-longer fit.

Even if I must mourn, for now, the unbeatable simplicity of owning such a device, and the unrivaled and unshakable trust I could place over it owning my day-to-day routine, I don’t think our world disallows such relationships from still forming today.

The only problem is that you have to create the environment within-which one can have that trust—nobody is going to sell it to you! And if anyone tries, well, you send them to me and I’ll let you know what I think!

Among its many features and drawbacks, there is one primary necessary facet to this trusty gadget—the Palm device which organized my life during the time when my life was the most organized it had ever been—which is, I still believe, translatable into the present: It is air-gapped.

Air-gapped. Fuck networking. Fuck TCP/IP. And extra-super fuck radio-waves. I don’t want to strobe a god-damned signature EM emission wherever I go! With the Palm, you sync changes to your personal computer with a physical cable or infrared light and sensor, like a TV remote.

Imagine that! A wire to connect and sync your device to your computer. How quaint!

The last twenty years of technological “progress” have been the gradual insertion of a million competing interests between you and the structures which organize your choice architecture. In other words, between your plans for today, tomorrow, next week, month, year, and the many cues and affordances in your environment which offer their divergent or commercially “enhanced” plans.

The nature of high-level, easy-to-use computing interfaces is to bury-and-hide the enormous, chasm-like gap which has been rent open between the average consumer and his or her daily routine and habits. The goal of any ethical computer literacy, then, should be to make that gap felt. And to leave you feeling sick with vertigo at its exposure, until you clamor to regain control.

The Machine at Work

I remember the first time I was out late at my buddy’s place in Hog’s Back, checking Google Maps to see when the last bus would swing by to take me home to South Keys.It must have been nearly a decade ago.

I plugged in his address, I plugged in my address, selected buses and the results popped up in less than a second.

There were only two choices. I had a bus in three minutes, and I had a coupon for an Uber gig-driver.

“Damn!” I thought. “I’m not going to make it out there in under three minutes! I guess I’ll have to walk.”

I don’t mind walking. I do it all the time—sometimes for hours. But something tickled at me. It seemed wrong.

I opened my web-browser and went to the OCTranspo website. I checked the digital equivalent of the old-school paper bus schedule for the route I wanted.

The bus kept running for another two hours.

I raged for twenty minutes at my poor friend, and vowed to never use Google Maps to plan my route ever again. And I don’t.

Physician, Heal Thyself!

The same dirty tricks that commercial software vendors use to manipulate you into buying dumb shit, or to pay-monthly to run on their dumb tread-mills after ever-receding carrots, must be learned by you. And then implemented by you on you.

If you are comfortable organizing your life entirely out of a paper notebook, then that’s that! You’re free! But there is no good reason for me to abandon the affordances of digital devices just because today’s crop is corrupted with psy-ops. They are, fortunately, still programmable.

Let me know if you’re interested in the particulars of how I have everything set-up. What I’d like to focus on in this piece, rather, is the structure and sources for how I’m thinking about designing my private, air-gapped personal Skinner-box. My externalized executive functioning.

In a perverse, extremely un-Clinton move, I have actually been hammering out this plan with ChatGPT. I know, right? What? Me using AI? Listen, listen, I basically never use the thing for anything. I am rather AI averse. Yet, at the same time, it’s not going away. So a while ago I got to thinking. It knows every trite self-help system and major book that’s been written. It knows all the contemporary pop-science on how to change habits, increase efficiency, etc.

We talked about Steve Allen’s Getting Things Done, which I unsuccessfully tried to implement a few years ago. Owing my intentions to organize my personal and creative life, instead of the professional office-work life which GTD is intended for, it suggested I read The War of Art by Steven Pressfield. So I did, and I brought up the points I found salient. Now, at its recommendation, I’m reading Atomic Habits by James Clear. That one is worth a few words.

Habits and Habitat

Two years ago, I read Tiny Habits by Stanford Professor BJ Fogg. I will give you a copy/pasted quote direct from my notes:

1/18/22 12:24 PM

This book is so wonderfully chocked full of robotizing post-human language that it practically signals a total re-instantiation of the mechanical age *as content* of the electric spectacular dream.

The anecdote about how "Linda" turned her life around with the tiny habit method is hilarious for underemphasizing the cult-like influence of the book, leading her to literally sell her horse ranch and sell her life story as a lower-rung of the author's pyramid, hawking his method as a licensed acolyte. And that's a *success story* the reader is to find *inspirational*! Literally "life coaching will coach you into being a great life coach!" IRL.

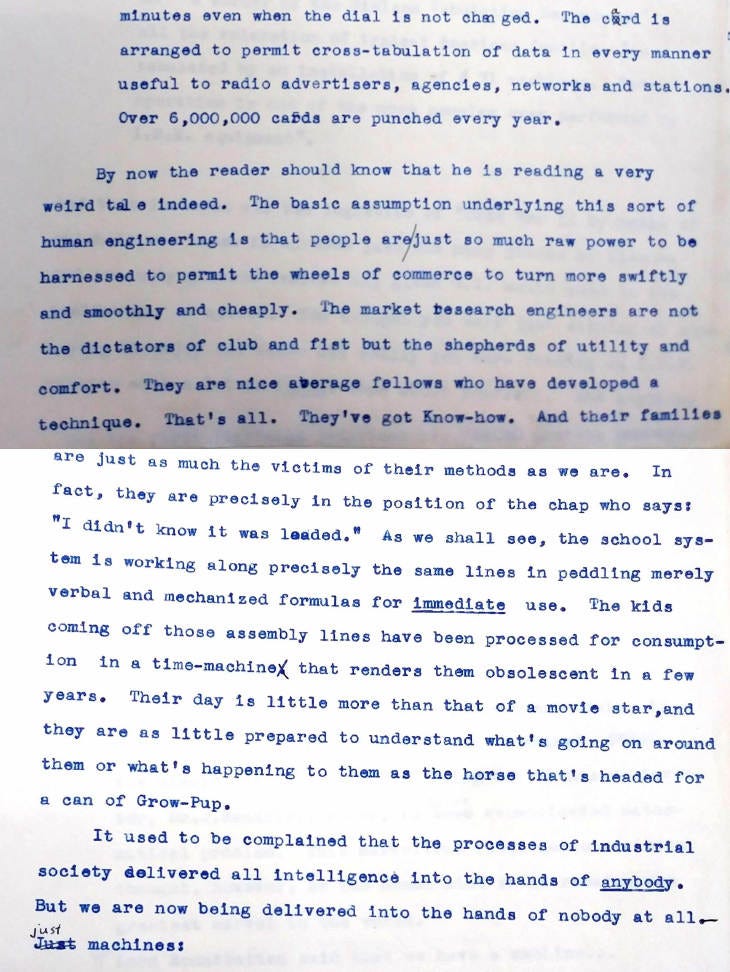

Now the book gets better after that, but not by much. I still interpreted it as the guy who lead the class which created the most brain-destroying software in the world trying to retroactively spin the work of his “Persuasive Technologies/Behavior Design” laboratory into a positive thing for personal emancipation. In McLuhan’s words, he’s one of the “nice average fellows who have developed a technique” featured in The Social Dilemma documentary from a few years back.

Atomic Habits has made two references to Fogg’s book. The first is a side-glance smile at Fogg’s anecdote about spending weeks developing a habit to floss a single tooth. The second is the a short summary and integration of Fogg’s book, with credit, within the larger atomic habits model of behavioral change.

Fogg, it seems, had found the need to rebrand his lab’s work from the unambiguously top-down label “persuasive technologies” toward the at-least potentially bottom-up, self-empowering label of “behaviour engineering.” Clear bests him not only in scope of his model of behavioral change, but also in having started with the goal of self-empowerment.

As I said before, I’ve generally loathed all models leading me to conceptualize myself as a behaviorist meat-robot, dancing to cues and prompts. But at least I’d rather the lesson be taught under the guise of staying in control of my life!

Convergent Media

I get the term “convergence” from the title and topic of a very-popular book in media studies, Convergence Culture by Henry Jenkins. Writing early about the transmedia landscape of today’s ubiquitous pop-fiction “universes,” Jenkins highlights how each individual fans who are immersed in cross-references between multiple, overlapping media are easier controlled and left-guessing than audiences of traditional discrete media.

His book opens with the perils of producing television shows in the ‘90s, as online fans guessed all the plot twists in Twin Peaks or paid for private detectives and satellite photos to get evidence for who had won on Survivor before the finale had aired. By contrast, nobody could anticipate what would happen in The Matrix sequels because you’d have to have played the Xbox game, studied the anime, and read the comics to even begin to understand what was really happening in them! His lesson to a media industry in constant competition to keep its audience captivated with surprise? Bury them in massive, broken up worlds to get lost in—world with many entrances and lacunae—and they’ll be yours again to toy with!

(Speaking of toys, don’t forget the merchandising!)

It’s the Black Box, Stupid

Jenkins begins the book by warning the reader against assumptions about his term “convergence.” It does not care about, he says, a single box which will have all of your entertainment needs in one. He’s talking about the convergence of content: how it is a fictional world is made more eminent by arriving through multiple portals. This is something that Disney has achieved with its theme-parks and board-books for decades, as Baudrillard well knew.

Convergence Cultures release was coincident with the beginning of the smartphone. Only a few years later, iPhones and Android devices asserted their dominance as a convergent box. That is explicitly what Jenkins is not talking about—he’s talking about fictional universes.

I don’t care about fictional universes, though. I care about the real one I actually live in. Where I am actually an individual with a life I’m trying to live.

What happens to me in this universe? What is relation to my environment when mediated through the convergent do-everything box? The one which sells my most intimate of data to large corporations for their mucking-about in?

What results is the digital twin, which I discussed with former McLuhan Centre Director Derrick de Kerckhove. When Facebook has access to my contacts and my location and begins finding events for me to attend, I’m not even the one doing the planning any more. A locus of agency begins to form, to converge, about me which is outside of me. A parallel executive functioning—a foreign prefrontal cortex—employs a stead pressure of soft-power to overtake the one inside my own skull.

Now hold that up relative to the convergent movement that Jenkins prescribes, that of fictional universes which come at us from all angles. Our bodies become the center of convergence of fictional worlds at the same time as our real world ceases to converge therein. Just as rapidly as fantasy takes us over, reality recedes.

It is this double-motion, I think, which creates “fandoms.” And it is how even real life takes fandom’s form.

Services allow your calendar to be filled up automatically by appointments. Events are recalled to you. Your shopping purchases are recommended and incentivized by personalized ads and discounts, all calibrated according to data gathered by reward-points cards. What you’ll watch, what local events you’ll know about, and whose personal-life you’ll be informed of is increasingly decided outside of yourself. You sit back, resonating node, experiencing your identity rather than being it.

It is you because you can’t take it off. You never “put it on” to begin with. To have externalized something, you had to have been proficient in it first. Someone who can’t cook for themselves can’t delegate their cooking—they were always dependent.

What the last generation delegated, this next generation knows as environmental—it’s always been out of their hands. Something as simple as auto-play is, for a child, a fundamental aspect of reality. Their primary power is in turning it off—the basic phenomenon of choosing what to watch, however, was not a primary experience which then became automated. The decisions were out of their hand by default.

Time to Build Your Way Out

I must argue vociferously against the idea that metaphorical “awakening,” in the “red pill” sense, is akin to the pulling of wool from one’s eyes. Or the fall of a curtain to just reveal what is behind. Or waking up from a night’s sleep and seeing the dim walls of ones bedroom.

That is not how perception works. Perception works by slow, deliberate, conscious training. It works by learning. Habituating. Graphic artists spend hours with pencils drawing ovals and circles and arcs and lines over and over and over for months at the start of their training. They must do this until they can begin seeing the world in these forms, so as to capture them in a single, automatic gesture. The automation of perceptive gesture comes with practice.

This is why you can’t just “take off” the digital twin when you never put it on to begin with—it always was you. You’d have to start the long process of learning to live without it as would a child who never had it to begin with. Only then can you merely have it, as opposed to be it, in Kegan’s sense.

Babies spend years learning to differentiate and perceive objects in the world which they can reach out to and grasp, or imagine exist even when hidden behind something else. We may interrupt and hijack that process in children with our object oriented computer paradigms today, but everyone still has some form of object permanence.

If you were slowly seduced into the Wonderland of fictional universes—be them from the entertainment industry, or be them from politics—then I suggest that the process of getting out of them is slow and deliberate. It is the process Clear outlines in Atomic Habits.

After all, the whole point of “sensing reality” is to gain control over your relation to your environment. Your habitat. Your room, and your home are in the shape of your habits—things are where you habitually leave them, ready for you to pick them up. You change your environment by changing your habits.

My one modification is to only use systems which you entirely control. Do not use cloud-services, or closed-source applications to manage your to-do list or calendar. Keep the details of your life as private as possible. Air-gap is the ideal. Keep the data-vampires guessing as to what your next moves are. Deny them everything you can.

It’s not about just going offline. “Unplugging.” It’s subtler than that. It’s knowing that your computer is an extension of yourself. That the details of your schedule and your habits are your digital twin, your executive functioning. And keep those externalized parts of you as close to your body as you can. Keep them on the hard-drive on your PC, and the memory of your phone. And nowhere further in a way which is unencrypted.

Remember the Palm Pilot! Remember what they took from you!

But don’t retreat to the past ever. As I said, I used ChatGPT to hammer out some details for better habit formation, based on all these books, using all locally-controlled, Free Software tools (at least, as much-so as is feasible today). After we worked out a long schedule of gradual steps, I asked it to make me an .ics file. ChatGPT informed me it couldn’t make such a file, the standard calendar format, but it could write me a Python script to generate one. With a few revisions and a quick sudo apt install python3-icalendar, I had an .ics file to import into my desktop and phone full of subtle habit-changing cue events for the next month.

I just asked the big, scary, world-threatening AI bot to build me a pathway out of the matrix… and it did.

How about that?

I’m not sure how to go about writing the more technical implementation details—this is more high-level theory stuff we’re into today. Would subscribers enjoy actual suggestions of what works for me now? Or would anyone with a more appropriate forum like to have me on to talk about it? Or is someone who is seriously interested in Free Software development looking for ideas? Hit me up anytime! :)

A digital twin never stops giving …

I would enjoy suggestions on what's working for you now 😅