I try to keep my ego slim and avoid getting easily slotted into a community or identity. These are not necessarily foundational principles for me; they are principles I adopted through the course of trying to regain some clarity and coherency of thought, body and mind during my psychotic break.

Maybe that’s weird. To “keep a slim ego” sounds kinda Buddhist, and avoiding identity labels sounds like individualism in some political sense, like I’m a libertarian or something. Those things—being a Buddhist or a Libertarian—are usually core identity traits as we talk about them, not second-order consequences.

But our environment entails constant openness to play. For reinvention within many different frames which span from our embodied relation to the immediate world up to dancing electric across the face of the globe. And during the prodromal stage of my psychosis—which means, the early stages where I was starting to crack up—the contemplation and rumination on these vast scales for being, for play, was what drove me to breaking.

(Yes, even though modern psychiatry looks at psychosis in purely biochemical terms—and has many good reasons for doing that—I find it useful to work on the psychodynamic side. At least I’m not outsourcing such contemplation to the internet or to some guru figure; we’ve seen where that goes!)

Everything I’m writing here on this blog is an attempt to recollect and regather, in words, what I was mutely thinking back then, incommunicable and terrifying. What does it mean that we’re amplifying ourselves into frictionless, limitless imaginary places every day? Delegating our thoughts to people and systems remote from us?

I decide that embodied me was the real me—even if he lives imperfectly at the smallest level that communications technology allows. (There are smaller-levels—but they aren’t social. They are the you that exist in, say, single-player games, or alone looking into your mirror when you aren’t preparing to go outside or even just go upstairs and encounter a family member room-mate.)

Finding words to eloquently express these ideas entailed a great deal of what McLuhan called “probing” of my social sphere and environment. I am constantly playful, saying things to get reactions, searching for the mot juste and delighting when one page in an otherwise useless book justifies having read the other 300 pages. There are puzzle pieces everywhere, mostly in the form of words. Some words are heard directly, but many are formed of from snatches of poetry one extemporates to capture some more ineffable experience. The world turns on clever phrases, to turn one myself.

Collecting those words is like collecting spun-sugar tendrils around yourself. I’ve built my body is made of candy-floss. It’s a silly metaphor, but it’s literally how I conceptualized my plan to “flesh” myself out—one delicate strand at a time, caught out of the air by being at the right place at the right time.

I wanted to work on the ground layer—“base reality” as simulation theorists call it—and then have any internet presence or larger “image” or “brand” derive down-stream, under some semblance my control. And I want my computer—the thing that contains my calendar and my todo list and every other algorithm which externalizes my executive functioning—to be under my absolute control. And so walking around and being myself was important.

One reason I have tried to do this was the startling realization about how different people use language. I want to speak for myself, and I want to speak with other individuals. In our more usual way of talking, I’d rather not be a “collectivist,” or “tribal,” or an NPC who speaks to “signal” some shibboleth of group belonging. Once I began noticing how many people speak and say things to establish rapport and identity, and not to grapple with the particulars of subject they’re discussing, I closed the door to self-diagnosing as autistic. It was a skill issue all along, not an innate medical condition.

Let’s, though, use a different framework for discussing this dichotomy between individual and group-member. Collectivists speak and perform to create the stages, or environments, for their continued performance.

The creation of environments is an art. Wedding planners do it, DJs do it, as do any other event-hosting role that may come to mind. Games are environments, whether they are video games or the role playing games planned by DMs. Even just doing customer service work entails creating a shopping “experience” for customers, speaking as the uniform I’m wearing. When I say, “I’m sorry, we don’t have that in stock, would you like to try this instead?” who is the we? It’s the corporate identity which I’m embodying.

What you’re doing in such public, one-to-many addresses, is speaking for the environment. Speaking as the environment. Shepherds and their sheepdogs change the terrain for the flock they herd.

The loudmouth, opinionated person who blurts out a partisan opinion about current events is setting the scene. They’re controlling the frame. Yes, it’s a signal about their identity, or belonging to some group. But, at the embodied scale, it’s a form of becoming the very space itself, of wrapping themseleves around the rest. It’s an inversion from being a single individual in a space to being the space itself within which bodies exist.

Environments are circumscribed. They are “framed.” In a closed-game, their is an arena of action where, if one goes to far, one is out of bounds and a time-out is called. The game is interrupted. It’s easy to see when one is talking about soccer—but what about discussion?

During the course of my psychosis, I was trying to relinquish control over my larger environment. I wasn’t sure, really, who was controlling who. I was trying to take control of the smallest environment I had—my body and bedroom or workplace or bar table—without losing it completely. Without losing society completely. But where is the arena? What is its boundaries?

In An Essay on Metaphysics, R.G. Collingwood has a fantastically straightforward definition of the title subject. A person’s metaphysics is the ground-level of their propositional rationalization such that, when you start questioning it, they get angry.

Ask someone a question they can answer about their beliefs and they’ll probably induldge you. Let’s assume you are being honest and they trust you. At some point, however, as you keep digging, they’ll stop playing with your silly questions. Even if they can’t assume bad faith on your part, they must eventually just get offended, or violent, or feel undermined and become thrown into confusion.

This is because, Collingwood says, metaphysics is the level of presuppositions, not the propositions which one has rationalized on top of them. Presuppositions are buried, in the ways that we speak to each other. They’re unconscious.

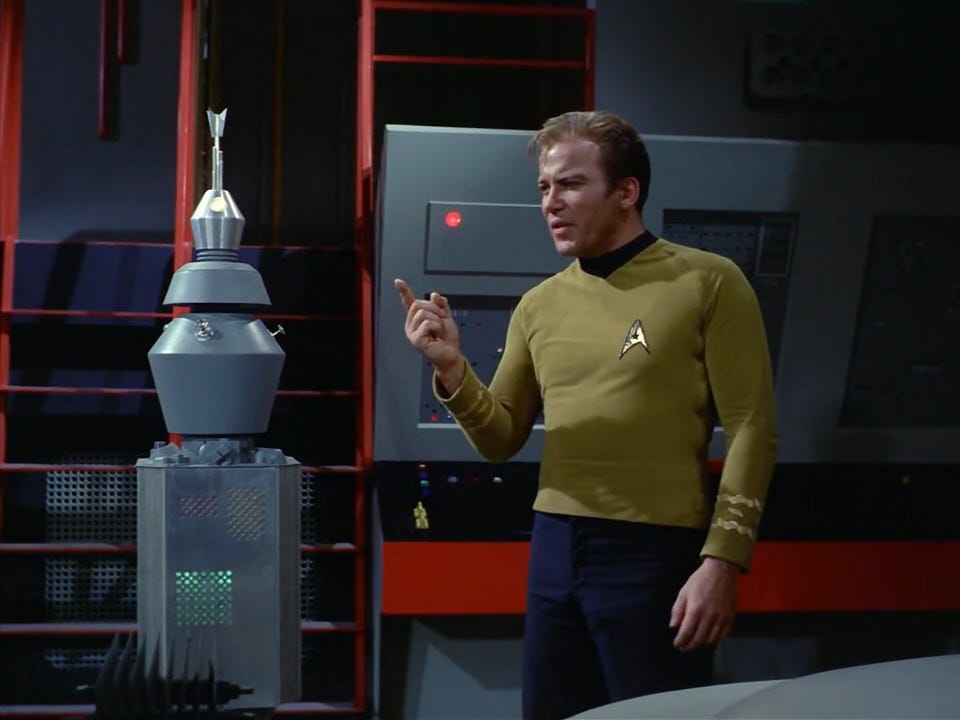

Now I’m not one for formalizing thought into logical rules, but this is a fantastic way to think about our embodied being using that that frame. It really captures the whole Captain-Kirk-talks-a-computer-to-death skill which every “debater” wishes to hone. It’s what the praxis of dialectic looks like. Two ideas enter, one idea leaves.

My strategy out of this arms race, then, was to carefully try and rebuild a metaphysics for myself premised on the presupposition that I am a materially-embodied human dude walking around in Ontario, talking to people and sensing and poking and prodding stuff with my fleshy-little limbs. I’m not going to be some simulation theorist—I’m not going to go all Descartes, disbelieving in the world itself. It’s enough to presuppose that my senses could be trained to get a dim idea of the immediate reality outside of me. And that reality will be a domain for play. For growth.

I had already learned how my computer worked growing up. Huge head start, socially-speaking, in understanding my local environment. I needed to find new things to do offline, touching-grass, to play with. To learn with. To win and lose at. I had to talk to people as though I was living at this local scale.

So that means I don’t really get into political discussions much, or talk about other big ideas. I keep that shit to myself. I had to go back to basics! When I talk about big things, I talk about them in relation to the humans living in relation to those big things. I want to talk about things proportional to the human scale.

People who are “larger than life” are, I think, an artefact of 20th century media. We’re in a new terrain now. We need to humble ourselves to the changing conditions, rather than ritualistically follow commoditized strategies for “success” at goals we’ve been mimetically programmed to desire.

I’d like to write a lot more about play, arenas of play, open and closed games, and embodiment—but what I' have saved in my drafts is too much too fast. I have a bad habit of writing as though I’m scribbling the last message-in-a-bottle I’ll ever lob to posterity.

But I am, in fact, trying to speak for your environment—just not your larger social one. I’d like to “host” you in the one you find yourself actually within, at the human scale. The one you were supposed to play with as a kid, Piaget-style, to figure out. The environment which hijacked your senses before you had any defense. The environment you don’t even know you’re missing.

And when you question people’s presuppositions, they get angry. They have to think, at least, you’re doing it in good faith. And they have to take time to re-equilibrate to the place you’ve shoved them into, the new relation to the world they weren’t ready to go. There is no ready. You will never be ready—if you were it wouldn’t work. It wouldn’t be liminal, and you won’t really be playing.

At the Media Ecology Association’s 2019 Conference, I attended a panel on, basically, #GamerGate. Professors had spent months preparing undergrads to begin reading 4chan without any risk of their seccumbing to right-wing propaganda. They reported on all the psychological challenges, the stressors, etc. on developing feminist corrective to innoculate their students. The students gave talks about their online field-work, giving their laughably-bad analysis of troll culture, misogyny, etc.

It was the most intense practice at sitting still and pretending to be quietly, happily listening which I had, up to that point, ever had to experience. The entire facade of academic competency was blown apart. It was a privilige, in a way, to sit there inside a room and get a first hand account of the problem. It’s what lead me to write the following in my last #GamerGate piece over on Default Wisdom:

Modern scholars today are quite aware of how amateur, shoddy, and often-time destructive anthropology was in its origins. The archetypal tale, as I understand it, is basically this: a random white guy shows up in some “unexplored' territory on a map and gets everything wrong.

He tortuously mangles whatever he can glean from the indigenous peoples and their cultures and customs into the shape of his own preconceived notions. Everything he doesn't get he just makes up, he takes some pictures, and then he gets famous back home selling books and speaking as an expert on these people. Then, one day, their descendants get exposed to the image he made up of their parents, and, to some degree, those ancestors begin to become the people he made up…

The world, it seems, did in fact need these credentialed anthropologists—the journalists and the experts—to explain the gamers to them. Because nobody outside the chronically online understands the internet, or video games at all, whatsoever. They only understand what's been “socially constructed” for them to understand about how this damn computer-thingy works, or what the damn kids are wasting their time and money on.

The world the gamers lived in was not the world the newspaper readers and cable news viewers and academics lived in. Each was in its own media. They lived in their own worlds, with different rules of physics, and different forms of embodiment. Of expression. They spoke different languages. They had different theories of mind and theories of communication. Different degrees of dependence on others, and dependencies for different things. Different decorums and different evaluations of respectability and merit. The anthropologists knew this abstractly as a professional consideration, they took it for granted. The gamers had to learn it from experience.

For you see, the gamers—those little empiricists—encountered other individuals as their own instances in-and-of themselves, with their own stats. Unique. Their world consists of individuals. The only way to know another individual is to play them.

The professors had a duty to not let their students get radicalized by internet propaganda. But they also were playing a losing game from the beginning—how are undergrads supposed to go learn to study an internet culture, such to speak from a more-knowing place about those people than the people themselves? Are posters in online forums so easy to get under a microscope? Can you train a 19 year old to do it? Who is looking at who? When the internet is trying to understand how everything got all “social justice” or “woke,” and the institutions are trying to study “far-right propaganda” and “Russian disinformation,” who has the advantage?

The problem is that these students have not, yet, learned to socialize with a wide-group of people in the flesh. They’re not living at human scale. And you sent them out to dance in an electric environment—to play in arenas which exist only in the mind, and are projected far beyond the bounds of the flat earth. Randy, at the Egg Report, writes

People live in very very very small worlds, compared to the size of the “world” ™. It is a cruelty to demand of them to contend with all of it all at once, all of the time. This is what being-within-media, today, is doing to you.

The human mind is not designed for a “closed” image of the world – neither in the sense of closed materialism, determinism, nor in the sense of a Fully Explored World. A “globe” is a “world map” that loops. We take it for granted that this is the case, because, we know that this happens to “be the case”.

This is whut mean “life is lived forwards, but can only be understood backwards”, by Kierkegaard. This is whut mean “rationalism can only be a handmaiden to the senses” by hume. This is whut mean “absurdity”, “leap of faith”, “existentialism”: It does not matter whether the world is round – we must act (as if it wasn't).

I agree with Randy. Even if some people can, somehow, sensibly scale up their lives without going off-the-deep end, can they do it without having mastered the human scale first? Without having learned the patience and humility of listening and communing with others in their small, local corner of the world?

Our technology, as most people use it, is pulling them inside out. I won’t say it’s the technology, I’ll say it’s how they use it. Because there is room for a lot of play in how they use it. You own a computer or a phone and you feel it’s ruining your life, your attention span, your dating prospects, etc.

You’re doing it wrong. It’s a skill issue.

There is no-one in the room except you and your computer. How about you actually play with taking control of it?

Crazy proposition, I know. But we used to live in a world of discrete media—radios and televisions and cassette tapes and satellite dishes. Now that they’re all the same thing, empowering yourself has never been easier. You can own the thing, if you work on yourself. If you stop projecting your into infinite spaces for playful development, and crawl back into your immediate world.

Stop performing arguments like you are rehearshing for a podcast, and begin searching for the form of the human-scale life you aren’t in control-of yet.

The more I practiced at talking about very technical and obscure things well, the better my socialization became. The more I was able to fit in and feel at home among different groups of people. The tech world isn’t more complex than any other subject people love to listen experts talk about—its just that the experts in tech are all insane from radical disembodiment.

They can’t speak in ways which reveal the environment. They are terrible shepherds because they don’t even know where you are. They are not good bases for attachment. The way they create games, and arenas for play is downright-uninhabitable for most people. They’re split across the computer stack and don’t even see the bottom.

You can’t become an authoritive speaker on a computer you can’t control, but you can make a system you can and speak to that. You can talk about it. You can speak technological environments into existence.

Our current generation of technologists can’t do that beause their business model depends on your ignorance. They need you to meet them three-quarters of the way.

In good faith.

real