Quick (and incomplete) History of Rhetoric

A botched experiment in trying to do things the proper way

Not only have I begun a full-time college course, I’ve also been packing and moving all month! So, I’m sorry for the slowdown in posts. Thing will pick up again once I’m settled in.

This is why I’ve decided to share this piece—which is both one I like a lot and yet also one which I cannot—for reasons you will discover—finish in its intended form.

When in doubt, go meta!

Exordium, or Introduction

A few years ago I picked up a monument of a book, published by Oxford Press, titled Classical Rhetoric for the Modern Student by Edward P.J. Corbett. Introducing his subject, Corbett writes

Almost every one of the major English writers, from the Renaissance through the eighteenth century—Chaucer, Jonson, Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden, Pope, Swift, Burke—had been subjected to an intensive rhetoric course in their grammar school or university.

While this is already an admirable length of time for a tradition, don’t be fooled. The art of rhetoric predates the Renaissance; it long-predates English itself. As the wonderful historical survey near the end of Corbett’s book informs us,

The art of rhetoric was first formulated, in Sicily, during the second quarter of the fifth century B.C. Corax of Syracuse is commonly designated as the first formulator of the art of Rhetoric… When Thrasybulus, the tyrant of Syracuse, was deposed and a form of democracy established, the newly enfranchised citizens flooded the courts with litigations to recover property that had been confiscated during the reign of the despot. The “art” that Corax formulated was designed to help ordinary men plead their claims in court… Perhaps the chief contribution that Corax made to the art of rhetoric was the formula he proposed for the parts of a judicial speech—proem, narration, arguments (both confirmation and refutation), and peroration—the arrangement that becomes a staple of all later rhetorical theory.

There are references in Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and Quintilian to the part that Corax and his pupil Tisias played in formulated rhetorical theory…

To the extent that we can consider the tradition of Corax to continue, it sounds like a 2,450 year tradition if I have my math right. But does it continue?

Everyone, more or less, has an informal idea of what rhetoric is. In his introduction Corbett identifies its centrality to advertising and propaganda. Dating this second-edition, he continues

The newest variety of dangerous rhetoric is brainwashing. A definitive analysis of this diabolical technique has yet to be written, but a beginning has been made in the terrifying final chapters of George Orwell’s 1984. A good argument for an intensive study of rhetoric is that citizens might thereby be put on their guard against the onslaughts of these vicious forms of persuasion.

What would make a study of rhetoric “intensive” would be a formality to its proceeding. A lesson plan. And such formality is exactly what classical rhetorical studies offers.

It overwhelmingly obvious, at this point, how this essay on rhetoric would be greatly improved. Improved not only in its claims, but also in its efficacy of persuading you that its claims were true. Clearly, I must not merely continue to talk about rhetoric. I must also “walk the talk.”

Thesis

So, how does one traditionally go about composing an argument in the classical tradition? The first chapter of Corbett’s book is titled “Formulating a Thesis.”

Oh no. Clinton never states a thesis. I just sit here and pour my thoughts out of my fingers into a scrollable window-pane until Substack warns me to pinch it off! I write in the soft, bottom-up, playful style of exploring my thoughts on screen. I create bricolage of words—I don’t formally structure arguments top down! To put it in the unsavory, reductionist paradigm that only mystics, feminist theorists, and male chauvinists find comfortable: I write like a woman. I don’t plan my writing with outlines!

It is worth a discursion here into the historical context of that idea—the “outline.”

Part of the nineteenth-century development in the teaching of rhetoric… was the doctrine of the paragraph, stemming from Alexander Bain’s English Composition and Rhetoric (1866) and fostered by such teachers as Fred Scott, Joseph Denney, John Genung, George Carpenter, Charles Sears Baldwin, and Barrett Wendell. Barrett Wendell’s successful rhetoric texts helped to establish the patter of instruction that moved from the word to the sentence to the paragraph to the whole composition. Henry Seidel Canby reversed that sequence, moving from the paragraph to the sentence to the word. It is to these men that we own the system of rhetoric that most students were exposed to in the first half of the twentieth century—the topic sentence, the various methods of developing the paragraph (which were really adaptations of the classical “topics”), and the holy trinity of unity, coherence, and emphasis.

There’s the formalism I hate! This is rhetoric at its low, not merely formulaic, but practically mechanical. Indeed, this is the point in the story, Corbett tells us, where rhetorical textbooks become replaced by handbooks. Style guides and lists of rules for “correct usage.” This is the milieu of rote linguistic technique against-which a young Marshall McLuhan stood aghast.

What thesis, then, shall I limit myself to in this piece? My thesis will necessarily constraint the scope of the rest of this piece. If it is too broad, I should type forever. If it is too narrow, I’ll not say half the things I’d like to!

I wanted to get into a bit more history—specifically the split between rhetoric as spoken and as written. I also wanted to use this piece as an excuse to spend an hour re-reading Richard McKeon’s Renaissance and Method in Philosophy; a piece central to McLuhan’s doctoral thesis on the classical trivium. And I would have liked to discuss the formal elements which are missing from contemporary handbook rhetoric (we’ll call it): the figures of rhetoric.

Now, we see, the reverse-engineering process begins. What point could I try to make which allows me to get into these—and hopefully only these—topics?

Maybe I should go meta. A fourth puzzle piece, I realize, may help me do just that. It is a long-misunderstood polemical essay by Marshall McLuhan extravagantly titled Have With You to Madison Avenue, or, the Flush Profile of Literature.

Okay. Yeah, I think I’ve got it.

Absent the acknowledgement of the centrality of classical rhetoric and its figures in traditional education, any claims to recognition, representation or restoration of a “Western tradition” is a laughable farce.

Boom! Shots fired!

Inventio, or Discovery

The rhetor, having decided on a thesis, must then gather the materials necessary to make his case. My research, in this case, is largely already done. What I write on this blog here is practice of putting my ideas into words. I’m literally rehabilitating my capacity for language here at Less Mad, because it’s not enough to just say what you think but to say it well. Say it to be well received.

What I have discovered through my intensive studies of McLuhan and the primary sources from-which he learned and developed his own thoughts is, largely, something of a restoration of what is now called the Western tradition. It is, as an ideal, a proportioned rationality which dances within all the tensions in life. Many dances are, in one regard, a play with gravity. Dancing is a graceful way of nearly always, but never quite, falling over. Dancing is achieved primarily through carefully sustained muscle tension against one’s own body-weight.

I’ve already talked about Ian McGilchrist describing the tension between left and right brain hemispheres as structuring our mind’s sensory relation to the outer world. And how, in John Bowlby’s attachment theory, oscillations in the “stalemate” of opposing “pressures” of comfort and curiosity develops the child’s ability to leave and return to the secure base of mother and father.

The sources that my speculations have selected for this piece—Corbett, McKeon, McLuhan’s Flush Profile—each deal in their own way with the tension between the individual self and the propagandistic, collectivizing environment which seeks to assimilate them into its thought.

This brings to mind one more rhetorically-potent element which I might bring to bear on my topic now that my thesis has been formulated.

There is a phrase derived from some verses in John 17 which instruct Christians to “be in the world, but not of it.” Apropos of my thesis, anyone who would define “the Western tradition” as being, at its heart, Christian really ought to appreciate the nature of the civilization in-which Christianity began. Hell, the work of spreading the word of the gospels is, quite literally, rhetorical work. Language, or logos, was already a highly-advanced secular art during the first century. Does it not seem obvious that an appreciation for the commonplaces of this civilization’s educational practices—the way that it created adults out of its children—is essential for understanding context of the New Testament itself?

Alright, this seems like enough material for now.

Dispositio, or Arrangement

Here I have a clarification to make. Up to this point I have been misleading you in claiming that this piece exemplifies classical rhetoric. If this were a proper bit of classical rhetoric, then it would not be organized according to the stages of how one develops an argument. It would be organized by the parts of discourse into which one classically arranges a text.

Here is what I mean.

In the “science fair” style of scientific writing which we all learned in elementary school, the organization of the written science report mirrors the actual linear steps of the formal method one took in formulating and performing the experiment (Ask a question, develop a hypothesis, design an experiment to test one’s hypothesis, perform the experiment and detail the results, analyze the results to form a conclusion).

This essay you are reading now began being written like that. I’ve started with the intention of organizing it into the five stages of developing a rhetorical argument. These are Inventio, Dispositio (we are here), Elocutio, Memoria, and Pronuntiato.

I did this because I am cheating. Because I’m actually bad at this. I’m either lazy or I’m rushed to get something out (one reason this piece is about rhetoric is because Corbett’s book is one of the dozen-odd books I have left-over in my nearly-empty bedroom, not packed at my new house). I’m making this essay up as I go along—I am not doing this properly.

The proper thing would be to, after working out the process through those stages which you are reading now, to begin writing the actual essay. This is just the prep work. A real piece of classical writing is not arranged like a science fair report, in accordance to the process of its development. It is arranged (if you’ll allow me the tautology) according to the formal structure of dispositio.

The parts of dispositio are:

Exordium or introduction (Proem in Greek)

Narratio or statement of facts or circumstances

Confirmatio or proof of our case

Refutatio or discrediting of opposing views, and

Peroratio or conclusion.

The remaining stages of development grow in irrelevance from here on out. Corbett doesn’t even bother giving elocutio, memoria, or pronuntiato their own sections—he instead finishes the meat of his book with a very-long chapter titled Style . We shall see why this is so in the following sections.

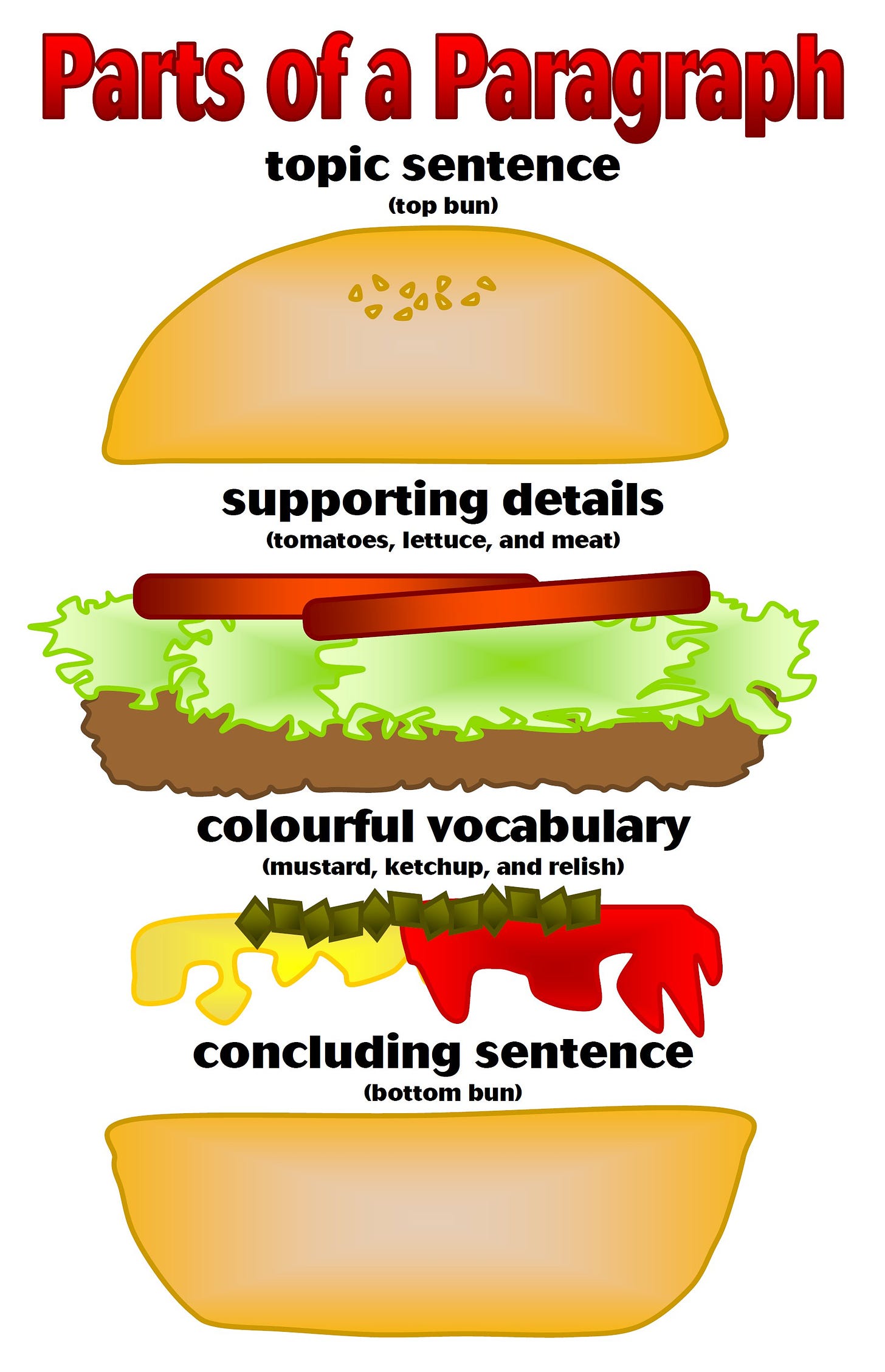

In fact, I will switch tracks and finish off the way that it should have started. The following sections will be planned ahead by me and written in accordance to the parts of dispositio. And thank god those parts are of a larger order than the stupid textual-paragraph hamburger of “topic sentences,” developing details, flourish-relish, and concluding sentence!

The classical “topics” out of which one builds elements are definition, comparison, relationship, circumstances, testimony, deliberation, and appeals to justice and to ceremony. These belong to inventio. And the elements of style, the figures of rhetoric, number in the hundreds. Proper, methodical study of these seems more important than dictating the Mad-Libs form of how to assemble a document. The topics and the figures are the real gifts of rhetoric which have been left behind.

Arrangement is the least interesting of all the stages. Which isn’t to say it isn’t essential.

Okay, so. I guess I need to make my case, discover within my materials some confirmations of it, find or generate and refute some opposing opinions, and polish it off with some final remarks.

Be right back.

Narratio, or Statement of Facts

Thanks for waiting. Ahem…

Absent the acknowledgement of the centrality of classical rhetoric and its figures in traditional education, any claims to recognize, represent or restore what might be called “the Western tradition” is a laughable farce.

There is much sub-standard ado about “the West” in our panicked public discourse. Conservatives grasp at straws to demonstrate any traditions relevant to our technological age, while progressives decry the oppressive and exploitative nature of the very culture which delivered them from the impoverishment of barbarism and liberated them from the shackles of ignorance and slavery.

In truth, none of what is argued about the West can be of much merit if the way in which it is argued is wanting. And, I assure you, wanting it surely is.

We netizens enjoy a rich culture of language—too rich, in fact. It is decadent. Since its origins as a digital dirt road, the information super-highway has been, like the telegraph networks which preceded it, “a speedway for words.” And like newspaper headlines since the late-19th century, it has been the poetic virility—the rhetorical punch—which has given words wings to reach the widest cultural saturation.

In this “age of grand delusion,” Bowie prays,

Lord, I kneel and offer you my word on a wing

And I'm trying hard to fit among your scheme of things…

But it's safer than a strange land, but I still care for myself

And I don't stand in my own light

Lord, Lord, my prayer flies like a word on a wing

My prayer flies like a word on a wing

Does my prayer fit in with your scheme of things?

Yet an age of schemers blind to the scheme of things, wingéd words, ladies and gentlemen, are for The Birds!

New coinages rain down upon us daily. The words and concepts which vie for entry into the common lexicon comprise nothing less than a popularity contest for the polemical poets who originated them. Encyclopedic etymologies of foreign-English phrases fill the pages of Know Your Meme while vitriolic partisan slurs linger odiously alongside the risible street slang of Urban Dictionary.

The last eight years of criticism-critical online rationality culture has, in its own ad hoc manner, popularized many terms to describe the rhetorical manipulations of institutional influence. The term motte and bailey is the latest addition to the quiver of categorizable fallacies from which the rationalist draws his charges—as though the speech act of identifying a fallacy implied an automatic refutation to anybody besides an internet rationalist. And there lies the problem.

The chaos of incommensurable concepts and the imperceptibility of any scheme of things, in fact, affirms the observations of the rationalist’s post-modernist nemesis. Tribalism—the very fact of language signifying group affiliation more than rational statement—demonstrates the state of total social construction to anyone with eyes to see it. The fact that we live attached within each others gaze, that we perform and spectate simultaneously within recursive theatres, is proven again every day.

Revisiting this post in the evening after work, I made an unfortunate realization. It went something like, “Wait a minute… David Bowie and Hitchcock’s The Birds? This is just another schizopost! Arggh!”

At this point, dear reader, that I realized I was trying to do my old thing in a fake put-on of an advanced style which I am only writing about, but cannot yet write in. I mean, these associations are way too fast and loose. And there is no patching this mess up. I’ll still share it, because I think it’s useful as a failed experiment. But I’ll otherwise abandon it—the essay that is, not the subject of rhetoric itself—and stop wasting both of our time.

I will at least note that I use several figures of rhetoric very well here. Certainly a lot of alliteration. On the more obscure side “…wanting it surely is” is a hyperbaton, or reversal of words from their normal order. And my dual-meaning of the literal and metaphorical word “wingéd” counts, I think, as a syllepsis.

Every list of rhetorical figures is different—there is no singular canon list. Books from the 17th century would often list hundreds. Here is Merriam Webster’s rather-short list. And here is the 1st century Roman Quintilian expounding on many more.

It will take me more study of Corbett and a lot more allotment of time for writing posts to develop the discipline to write a proper, rhetorically-structured post. Probably with a way better-formulated thesis than the one I cooked up above—this initial foray into political polemics is cringy as hell.

But we’ll get a properly formulated essay out of me one day! Maybe it will need to be drafted in hand-writing…

Read this last night before I went to bed (I’m in Asia), then I listened to the audio version on the way to my Sunday morning supermarket run. This is a great meta experiment, it reads like running through your mind but not like a stream of consciousness. Lots of good references. Your substack is my favourite these days.