The Vow-Breaking Fruits of Abraham Maslow

Why human nature isn't actually progressing toward self-actualization

Everyone has heard of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

I’ve had a few pieces on it sitting in my Substack draft folder for weeks. The reason I haven’t published them yet is because they’ve really needed more review and confirmation—always double-check your secondary sources, folks!

This Tuesday, popping into some used bookstores downtown with a friend, I found a copy of Maslow’s famed Toward a Psychology of Being (first released 1962). Now that I’m a third of the way in I can finally begin validating and ponying up the goods.

But first, since I’m overdue on an effort-post, here are some immediate reactions from this extraordinary book.

Well, Ackshually…

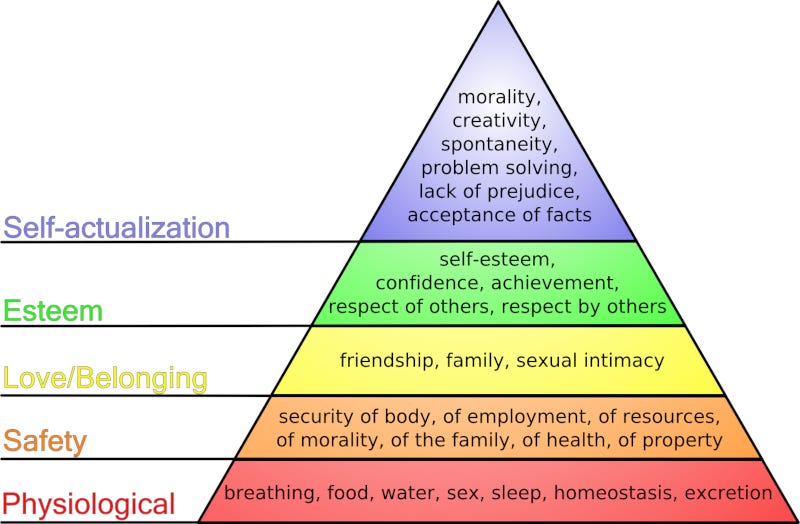

You’ve all seen this stupid thing before. That you have seen it, and that I know you have, is material proof of something very important: Maslow’s influence is larger than most of the influential names in psychology whose ideas most people know well and discuss and only wish we could apply.

The breadth of Maslow’s influence not in intellectual discourse, but in the real, practical world of applied knowledge. Many thinkers are endlessly read about in text books and written about in think-pieces. By contrast, while nobody reads or writes much more than a paragraph or two about him anywhere, Maslow is manifestly present in every organization we have. He is baked into the very structure of our world itself. That’s influence.

I’ve got a much more poetic and expansive exploration of the famous image above already written in an upcoming post. So for now I’ll cut straight to the chase: this image does not appear in Maslow’s most famous, best selling book. I flipped through it—it’s not there.

Turns out he never drew this stupid triangle; Arjun Gupta tells us it was drawn by a professor at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. Because of course it was.

Needs, Emotions, and Capacities

Let me explain what the basic needs really were to Maslow.

They weren’t, of course, merely a mechanical dependency algorithm, or checklist for ameliorating poverty. He wasn’t focused on getting all the bottom layers in order—he was always looking at the top. It was a psychological theory of mental health, not a theory of pathology or illness—other psychologies had dwelled on sickness for too long. To make up for that, Maslow only studied people whose basic needs were already met.

Maslow’s needs are all the things we need in order to muster the courage to self-actualize. Which meant, for him, to become our real, authentic, instinctual and spontaneous selves. In the pop-American onion-theory of psychology which Maslow bequeathed to us, all of our layers of fakeness are more-easily peeled-away once we secure everything below self-actualization.

And Maslow promises, after the fake is peeled away, what’s revealed is inevitably good.

When we have deficits in the lower needs like food, shelter, love, and self esteem, we develop neuroses and bad habits and hateful thoughts as compensation. In fact, Maslow calls these needs deficit-needs. Filling them just returns us to equilibrium, to stasis, until we grow deficient in them again.

The motivation to meet a deficit need is, in cybernetic terms, a negative feedback loops. It regulates toward homeostasis. I’m hungry→start eating→I’m full→stop eating→I’m hungry again→start eating again… Animals are motivated purely by deficit needs, and so long as we are too, we are basically animals ourselves.

But once all our deficit-needs are secured, our true self is free to emerge. That is, the innate, enlightened human self, which elevates us above animal instincts. It is uninhibited and free and spontaneous. Unconstrained by fear, by a need for security, this higher-self is alleged to chase after positive feed-back loops of continual growth and exploration. More leads to more, new leads to new.

And again, as it fortuitously turns out, the self-actualized person’s whims just so happen to align with the good and the right and the just. This being so, the self-actualized individual can validly issue themselves their own license to break-free of society’s rules and make their own way. This works because, as Maslow explains in the books opening:

This inner nature, as much as we know of it so far, seems not to be intrinsically or primarily or necessarily evil. The basic needs (for life, for safety and security, for belongingness and affection, for respect and self-respect, and for self-actualization), the basic human emotions and the basic human capacities are on their face either neutral, pre-moral or positively “good.” Destructiveness, sadism, cruelty, malice, etc., seem so far to be not intrinsic but rather they seem to be violent reactions against frustrations of our intrinsic needs, emotions, and capacities…

Since this inner nature is good or neutral rather than bad, it is best to bring it out and to encourage it rather than to suppress it. If it is permitted to guide our life, we grow healthy, fruitful, and happy.

Self-actualized people don’t need anything from you, or from the world. Their needs are met. They don’t need you. Thus, they are free to see you more authentically, more fully, for who you are.

The un-actualized—everyone else still stuck on meeting their deficit needs—can only see others as tools. They’re drowning, and so you’re only their life-preserver. A means toward their ends. If you aren’t useful to them, they are happy to ignore you or screw you over.

It’s only the person who can think selflessly—who has the comfort and security of having all their basic needs fulfilled—who can risk encountering the fullness of others beings and recognizing their innate value and worth. Of truly loving others for who they really are.

And so they do, Maslow says, as a matter of course. Well they do, don’t they?

Peak Experiences Without Valleys

Marshall McLuhan observed, in the French symbolist and English modernist poets he exhaustively studied in the 1940s and early ‘50s, a self-punishing disposition toward the world and the truth. The term he would often use is “self-abnegation.”

abnegate (v)

1: deny oneself (something); restrain, especially from indulging in some pleasure; "She denied herself wine and spirits" [syn: deny, abnegate]

2: surrender (power or a position); "The King abnegated his power to the ministers"

3: deny or renounce; "They abnegated their gods"

(Wordnet 3.0)

In a September 5th, 1935 letter to his mother in response to her “alarm” about his “religion-hunting,” a 24 year old Marshall gives us his meaning of the term abnegate. His brother Maurice had just enrolled in Emmanuel College at U of T in order to become a minister in the protestant United Church of Canada, while Marshall was slowly growing into his life-long Catholicism (non-italicized parenthesis are McLuhan’s, italicized square-braces are my own):

I have an uneasy suspicion Mother that you regard the United Church as an almost respectable profession in which oratory and humanitarian rhetoric can win the applause of good solid prosperous folk. You view with horror the idea of introducing religion into those auditoriums so well designed to exclude it. Let me tell you that religion is not a nice comfortable thing that can be scouted by cultivated lecturers like the Pidgeons [E. Pidgeon was minister of St Augustine Presbyterian Church in Winnipeg; his brother G. Pidgeon that of Bloor Street United Church in Toronto]. It is veritably something which, if it could be presented in an image, would make your hair stand on end.

Hence the fate of those poor uneducated undisciplined devils who stumble upon some of its “horrors” (they cannot administer the sacraments to themselves nor to their followers) while remaining inaccessible to its resources. Such was Bunyan and countless others. It is no wonder that men unable thus to see God and to love, quickly rationalise their beliefs as has happened in all the older Protestant sects. Men must be at ease in Zion if they are to pay more than a flying visit. The 17th century: Protestants abandoned the world and the flesh to the Devil and packed up for Zion. They found the climate there impossible and returned to earth only to discover that the Devil had been making hay.

That is the origin of predatory laissez-faire commerce: “Industrialism establishes a state of slavery more corrupting than any previously known in the world because the master is not a man but a system, and the whip an invisible machine. With this it is impossible to enter into any but inhuman relations, and in such an inversion of humanity all the instincts become perverted at their source” —Osbert Burdette [The Beardsley Period pg. 268]…

Maurice has chosen to become a minister in the Church of Christ. There can be no question of a career in such a choice. Abnegation is its definition. Such a choice unaccompanied by apostolic vows of chastity and poverty becomes almost meaningless.

In his unfinished book on T.S. Eliot from the late ‘40s, Great Tom, McLuhan spends a great deal of time exploring the broken minds of artists all-consumed by the horrors of the world (a more recent public figure alludes to his “grapple with God” in with likely-similar intent). McLuhan ties together Eliot’s simpering, ambivalent and impotent Prufrock and the sturm und drang—or violent, manic-depressive angst—of Laforgue’s Hamlet. He quotes the French writer Paul Valéry on the subject of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, first in the context of the European psyche shattered by World War I, and then from Valéry’s Variation sur une Pensée de Pascal:

Certain men play the Pascal. Convention has made him a sort of French and Jansenist Hamlet. Holding his own skull in his hands, the skull of a great mathematician, he trembles and dreams on a platform facing the universe instead of Elsinore. He is seized by the harsh winds of infinity; he delivers monologues on the brink of the abyss, exactly as from the boards of a theatre; and he argues before the whole world, with a ghost of himself.

The floating figure-without-ground of cyberspace seems captured here with an eerie uncanniness, does it not?

In these tellings, the desire for knowledge, or the commitment to love or to truth, come with sacrifice and consequences. Often terrible consequences. And first comes the sacrifice, and then the revelation.

Self Expression and Perception

What McLuhan saw in the development from symbolism in modernism was the harnessing of such a state, through dedication, toward a birthing of keener perception and higher art. From the same source, McLuhan writes:

…generally speaking our age has so crude a concept of the creative act that it either disallows anything creative to be present in ordinary intellectual perception and learning, on the one hand, or it applies it whole-hoggishly to salesmanship and toilet habits for tiny tots. There is nothing unusual today in the spectacle of intellectuals who are so ashamed of their pursuits that they take time off to prove their essential virility by improvising some botch on a canvas, some informal essay masquerading as a poem, some arid little tract disguised as a novel. Such persons are still bedeviled by the early romantic notion of creation as an out-pouring of some sort. That was a merely psychological idea of art devoid of metaphysical perception…

In this antimetaphysical, Kantian scheme “creativity” consists in the imposition of form on the opaque and formless. And to the modern romantics creation means pouring their experience into an intellectual mold…

It cannot be insisted too much that the main artistic stream since Flaubert has been fed by radically different assumptions, and that not a page of Flaubert or Mallarmé, Joyce, or Eliot would exist in its present form if they had held any such notion of creation as an outpouring of their experience into a conceptual framework.

Maslow has it that expression of the authentic self, arising after all basic needs are met, brings about a deeper perception of the world automatically. Yet, in his book, he often gets right up to the truth before suddenly failing to see. For instance, he cites a psychology paper from 1951 containing some very interesting scientific hypotheses on perceptual development, some of which read

“A primordial aspect of the structure of the percept is differentiation between figure and ground.”

“It is possible to control experimentally the phenomenal aspects of the genetic process i.e., to teach the subject how to perceive.”

“Integration tends to achieve homeostasis or stability and offers maximal resistance to change.”

“By varying experimentally the exterioceptive, interoceptive, and proprioceptive components which affect perception, one may define a full continuum from realism to autism.”(!)

“The more complex phenomena of conflict, ego-defense, and psychoanalytic dynamics generally may be viewed as anchorage and differentiation phenomena in which two or more aspects of a perceptual field can make a sharp bid for the role of figure.”

All of this goes a great way to prefiguring McLuhan’s later statements on media and mass somnambulism, and the artists role in pulling new figures out from the ubiquitous and unremarked-upon ground. Human perception is learned. Gradually. Accurate perception is taught—learned from mastery of a tradition which built something worth learning and teaching.

Perception itself is an act of ignoring everything you’re not focusing on—an act of closing your aperture. Psychosis is the opposite—it’s the breakdown of the sensory gate, wherein the ground floods in.

But Maslow doesn’t seize the chance to talk about training perception. There is no mention of long periods of discipline or practice. He mentions, off hand, a preference for privacy among the self-actualized, but he only chalks this up to a self-sufficiency.

So-called learning theory in this country has based itself almost entirely on deficit-motivation with goal objects usually external to the organism, i.e., learning the best way to satisfy a need…[Such] associative learning and canalizations give way more to perceptual learning [here-citing above-mentioned 1951 paper], to the increase of insight and understanding, to knowledge of self and to the steady growth of personality, i.e., increased synergy, integration, and inner consistency. Change becomes much less an acquisition of habits or associations one by one, and much more a total change of the total person, i.e., a new person rather than the same person with some habits added like new external possessions.

This kind of character-change-learning means changing a very complex, highly integrated, holistic organism, which in turn means that many impacts will make no change at all because more and more such impacts will be rejected as the person becomes more stable and more autonomous.

The most important learning experiences reported to me by my subjects were very frequently single life experiences such as tragedies, deaths, traumata, conversions, and sudden insights, which forced change in the life-outlook of the person and consequently everything that he did…

To the extent that growth consists in peeling away inhibitions and constraints and then permitting the person to “be himself”,” to emit behaviour—“radiantly,” as it were—rather than to repeat it, to allow his inner nature to express itself, to this extent the behavior of self-actualizers is unlearned, created and released rather than acquired, expressive rather than coping.

Maslow frequently describes a confused mess of traits which may be associated with artists, saints, and great figures in history. But he makes a great leap by supposing that life experiences which collapse an ego bring about such higher states of being (so-long as the person has food, shelter, and love).

He sees their uninhibited self-expression as something arising biologically or psychologically. He wouldn’t expect a novice-pianist to just pound-out a Bach fugue after suffering a personal tragedy which somehow lifted his inhibitions. So how could the expression of any inner-self—if there is such a thing—come about through so mechanical a process of disequilibration and re-integration alone?

Again and again, it’s all about the person as a figure, existing in relation to some vague haze of culture and society and ideas which permeates them and then comes “pouring” out of them as “personal expression.” It’s all content. It’s ideas in books without notice of the books, role models in mass media without mention of the underlying media.

Again, Maslow gets right up to this point, but doesn’t follow through.

The most efficient way to perceive the intrinsic nature of the world is to be more receptive than active, determined as much as possible by the intrinsic organization of that which is perceived and as little as possible by the nature of the perceiver. This kind of detached, Taoist, passive, non-interfering awareness of all the simultaneously existing aspects of the concrete, has much in common with some descriptions of the aesthetic experience and of the mystic experience. The stress is the same. Do we see the real, concrete world or do we see our own system of rubrics, motives, expectations and abstractions which we have projected onto the real world?

Yes! Exactly! And, so… is everyone who is well fed and has a loving family going to magically start investigating, dispassionately, “the intrinsic nature of the world?” Going to suddenly develop an insatiable, growing thirst for knowledge, and a faculty for perceiving, the multifaceted nature of all things in endlessly generated analogies? For taking apart and understanding inside-and-out, oh let’s just say, the most complex object we ever made and surrounded ourselves with: computers? How the hell does he expect that to just happen?

The superficial qualities of the self-actualized he describes can just as truly be enveloped within the disembodied cyberspace of frictionless information flows, or the convergent, fictional universes of popular culture. And in fact, it’s more likely to happen because you don’t have to leave your house to do it. You said self-actualized people enjoy time alone, right Maslow?

You know what? I’m not being fair to Maslow—it’s really his popularizers who are to blame here. As a society, we’ve jumped straight to the rhetoric of self-actualizing without even warning of the necessity of the meeting all the prerequisite needs. We are prescribing that people emulate the behaviour of self-actualizers—which goes against Maslow’s definition of the self-actualized as those who do not copy or ape socially-prescribed roles.

All we really have, here, is a recipe for self-actualization in a virtual world which than has problems manifesting, or incarnating, in the embodied world of actual social living and survival (and object permanence).

The First Cut Is The Deepest

Discussing the effect Edgar Allen Poe had in inspiring the French symbolists, with his invention of the detective story

One of the principal technical innovations of modern art was made by Edgar Poe, a fact fully appreciated by the French, who had the wit to follow him, and by Joyce, Eliot, and others who had the resources to follow them… Poe invented the detective story, and, by implication the movie camera which artistically speaking brought the novel to an end. For the detective story and the movie camera are alike in that the “mystery” is “solved” by arranging “stills” [shots] (investigation of clues) and then having them set in chronological sequence (montage) the sleuth “reconstructs the crime” for himself and his audience merely by running of the “film” so constructed. The criminal is automatically (cinematically) revealed.

But this is the least important aspect of Poe’s discovery, being a mere by-product of what he saw to be the supremacy of effect. And a story or poem to produce a single effect, to have the utmost unity, must also be written backwards. Anything not conducing to that effect can by this procedure be eliminated and maximum intensity can be achieved. A further consequence of this discovery was developed by Mallarmé who saw that a poetry of effects was necessarily impersonal. The author effaced himself above all in not assigning causes or explanations as transitional devices of a novelistic and a pseudo-rationalistic type between the parts of the poem. Poetry could free itself at last from rhetoric and the novel. Insofar as a rationale of poetry was needed it is to be found naturally in the analogical drama of the very act of the intellect itself in making poetry…

To make an existential drama from the analogical activities of the mind in making (and reading) poetry, that is what is meant by “pure poetry.” But “purity” implies no exclusion of the common place. Quite the contrary. Mallarmé saw at once that for all this new art all existence was grist. The unconscious symbolist technique of juxtaposed items in newspapers he heralded as a parody of poetry, a very different thing from the opposite of poetry…

The esthetic error of the past said Mallarmé was to try to get efficient causes into the work of art as a means of rendering attitudes and actions plausible. But real poetic plots have no need of extrinsic causes. Yet most of the exegesis of Joyce and Eliot has so far been occupied in providing just such “causes” or copulas for the imagery and characters. At that level of novelistic awareness any old “plot” will do. The more the merrier. Dozens of such plots can be almost equally relevant simultaneously. For example, the initial situation in Prufrock or Gerontion is inclusive of every mode and metamorphosis of schizophrenia from the shaman to the mad and the poet, on the one hand, and of every combination of ultimate disappointment and rage, on the other hand.

The artist pulls, from the unacknowledged, unremarked ground of our collective sense-making, bits and pieces which present a revelation when merely juxtaposed. The stories of the telegraph-press taught Mallarmé this. As McLuhan wrote later,

Now was the time for the artist to intervene in a new way and to manipulate the new media of communication by a precise and delicate adjustment to the relations of words, things, and events. His task had become not self-expression but the release of life in things. Un Coup de Dés illustrates the road he took in the exploitation of all things a gestures of the mind, magically adjusted to the secret powers of being. as a vacuum tube is used to shape and control vast reservoirs of electric power, the artist can manipulate the low current of casual words, rhythms, and resonances to evoke primal harmonies of existence or to recall the dead. But the price he must pay is total self-abnegation.—McLuhan, Joyce, Mallarmé, and the Press, Sewanee Review, 1953

That sounds a lot heavier than Maslow’s formulation, doesn’t it? Maslow didn’t mention any price to pay. McLuhan naturally understood that the “rewards” of perception required making a choice and sticking with it. Owning such a decision means accepting all of its consequences—just as a priest demonstrated his faithfulness by his “apostolic vows of chastity and poverty.”

A Sense of Scale

Ultimately, I think Maslow was unable to make the leap to appreciating how much the role of change in the “self-actualized” person was purely about exposure to the infinite expanse of what is to be encountered and understood about the world outside of ourselves. He often states as much plainly, but then retreats to observations limited to describing the self-actualized individual as some kind of ever-changing, self-creating, protean visitor to the world. Never the world itself.

Thus, don’t get the sense that the self-actualized man could ever commit himself to anything, so-as to be reliable or dependable. He’s a flight-risk. He’ll grow bored, jump to the next thing as soon as it comes along. The reasons he loves others for who they really are is because he has no motivation to be reductionist or instrumental in the relationship. And so apparently, he will be good to them by default. Because being neutral or good is innate to humans, Maslow thinks.

But his self-actualized people have no reason to commit to others long-term. They don’t need to take vows, or honour them—because they don’t need anything. The self-actualized person appears to just do whatever he wants on a whim and it’s good because they’re self-actualized. If he leaves you, it’s good. It’s what he wants. It’s the spontaneity of the action which proves this—it’s on a whim, done without coercion from without, and so it must be the “real self” acting.

The ease with which Maslow’s self-actualized person acts results solely from the lifting of repression. The self-actualized person doesn’t care what outside-authority thinks. And so this ease, it follows logically, must not considered to result from any long, grueling training period wherein a skill is mastered, or any deep study of a tradition or code to be internalized and embodied, or any vow to be sanctified and renewed until death. The quick, decisive action of the self-actualized individual is not, than, anything difficult which is only made to look easy. It must be easy—or they’re not self-actualized in Maslow’s sense.

Furthermore, tragedy seems not to befall the self-actualized person. He or she has all their needs met, and so is endlessly resilient and unfazable.

The person at the peak is godlike not only in sense that I have touched upon already but in certain other ways as well, particularly in the complete, loving, uncondemning, compassionate and perhaps amused acceptance of the world and of the person, however bad he may look at more normal moments.

Such a mode of perception, wherein the self-actualized subject and the whole universe exist in harmonious relation of pure understanding, reads here like a purely hypothetical concept to Maslow. But, worryingly, he speaks of it as a healthy state of being. There is no weight, no Cassandra complex, no survivor’s guilt, no anguish or horror or dread of responsibility or irretrievable loss. Among the self-actualized, nothing is unacceptable. Nobody is Hamlet. Nobody is mad.

Artists Hurt

Again, maybe my problem isn’t with Maslow so much. Following his logic more rigourously, maybe my problem is with how the rhetoric self-actualization is preached in a world where all the lower needs remain unmet for everyone receiving it. If everyone’s self-esteem is fake and love uncertain and food and shelter at risk, then of course they can’t handle a raw, unflinching perception of everything high and low in this world. And perhaps their view that society is oppressive and wrong is wrong and self-serving of an ego that actually needs to be challenged and corrected by a little normalization.

Maslow was a utopian. I’m not. I can’t hope that enough people will suddenly have all their needs met before being able to handle seeing the truth about things. Maybe this is why McLuhan resonated more with me. McLuhan’s artists, toiling in the secular domain of showing us what this world is made of, were definitely not secure. They were not role-models for being upstanding citizens, people to emulate. They had calamitous relations and periods of hunger and exile and madness. But they also made art which revealed truths and progressed the human spirit. It often broke them. It did not make them gods of the charismatic, self-expressive sort Maslow paints a picture of.

That’s not to say that breaking people turns them into artists. Or that art is good when it comes from broken people. Whether or not the world broke them, or the selflessly broke themselves pursuing something higher, what made them artists was their commitment to exploring an ever-more nuanced perception of the world outside of themselves, while remaining functional and secure enough to finish their projects. It was their acceptance and fulfillment of a duty, to the sacrifice of other desires. Even other needs. It was commitment.

Orson Welles was once asked if poverty had helped his creativity. Aiming an easy pot-shot toward at romantic ideas about starving artists he answered, in a tone of definitive authority, “Uh, no.” The poverty, however, was not his choice—it was not a necessary price that he willingly paid in order to make art.

Go get ‘em, Tiger

There used to be a trope in movies where young and inexperienced characters resented being condescended to the older, more seasoned veterans or pros. The last example that comes to my mind is Jay in Men in Black loathing the anticipation of being called “Tiger,” and that came out 27 years ago.

That doesn’t happen any more—young characters resent being misunderstood. The older characters are allowed to have “forgotten what it was like” to be young, or to have lost touch. Or they can look upon the innocent with haunted, knowing eyes—perhaps try to give some cryptic warning or advice to the unprepared novice. But they can’t justifiably act smug and dismissive of the young and foolish. An overt, socially-enforced and normalized superiority of the knowledge of the experienced over the inexperienced cannot be validated by the film.

Firstly, movies aren’t made to validate old-people’s experiences (at least not of those kind). Furthermore, old people enjoy fewer and fewer practical affirmations of the reliability of their intuitions with each passing year. It’s no longer believable.

Old people are not being left behind by changes in human nature. The idea that human-nature itself is progressing upward is a new-age conceit by the charlatans who appropriated Maslow for his scientific cred (more on that later).

Every generation, rather, eventually falls behind in keeping up with imperceptible changes in the material environment. That environment includes, but is not constituted by its media content. Yes, ideas are changing, but the substance behind those ideas is where the ground is.

Mallarmé saw what the newspaper meant before anyone else, and ended the narrative copula. The newspaper showed people the world in the form of telegraphed snippets thrown together on a bundle of pulp on their doorstep. Everyone else saw the world, he saw the snippets and the pulp and the paucity of what could be conveyed in a few seconds of electric doot-doooot-dooting across a transatlantic cable.

Today we still imagine we are seeing the world itself in front of us each day, but in what form?

Self Expression is Risky

If there is some merit to Maslow’s concept of the self-actualized human, it is poison to most. The need to live in reality—and not romantic fantasy or technologically-manifested visualization of the abstract—is probably pretty important for cultivating whatever “inner self” which is going to be unleashed upon the world.

An inner-self which is grounded through study of traditions of wisdom and grace and trades and crafts and arts and the myriad technological disciplines is probably preferable to what screens blare at us by default. More desirable nourishment for those who adopt real-world agency—and thus assume the burdens of responsibility.

We may lament people acting as though their life is a movie—but at least such-people are pretty easy to spot, and their work largely neutralized in the performative, superficial and aesthetic realms. People who prove that they perceive and understand enough to actually upset conditions in the “real” world are much more worthy of attention.

And if we aren’t all good on the inside, as Maslow predicates, then all the more cautious the rest of us should be. No wonder such conversations universally end up invoking religion and traditions. McLuhan saw the Pidgeons (the progressive protestant ministers) as running social clubs instead of churches. To take something seriously entails giving up a whole lot of everything else. And, believer or not, you must admit it stands to reason that the salvation of others’ souls ought to be something worth taking very seriously to anyone who would assume such a responsibility.

Presumably, what we want from the people at the top of our hierarchies is such a sense of duty for the rest of us. In the secular domain, the fashioning of our world is an artisanal endevour. And so art from such people conceived as self expression, made evidently as “some botch on a canvas, some informal essay masquerading as a poem, some arid little tract disguised as a novel” is hopelessly discouraging for the rest of us.

Poverty or self-inflicted injury should not and must not become some social signal of competence or artistry. Keep that shit to yourself. Have some dignity. It’s not for the public to know. Yet at the same time, how can your commitments mean anything to you if you don’t actually feel the price you’ve paid to keep them?

And when the ground keeps shifting, what’s more important in the world of art than the solemn and self-less duty of continually find and re-establish the firmament which lays beneath?